What is lychee?

The lychee tree belong to the Sapindaceae family, has an unmistakable appearance with its dense, rounded canopy filled with glossy green leaves that bring a refreshing splash of the tropics to any setting. It can reach up to 40 feet when fully mature, though in some cultivation practices, pruning keeps it more manageable. Lychee’s leaves are pinnate with leaflets that grow in pairs, showing off a rich green hue on the top and a paler underside. This visual appeal adds a tropical touch to gardens, patios, and orchards, especially when the tree is healthy and thriving.

One of the key characteristics that make Litchi Chinensis so remarkable is its lifespan. Properly nurtured, lychee trees can live for several hundred years, continuing to produce fruit well into their lifetime. This resilience is a testament to its genetic strength, which is why the tree remains so popular and valuable.

How to pronounce lychee?

The way I pronounce lychee is “lee-chee,” which feels more natural and less confusing when I’m ordering it at the store.

What does lychee taste like?

To me, lychee tastes like a tropical blend of grapes and roses, with a hint of citrus that makes it refreshing.

How to eat lychee?

I usually eat lychee by peeling off the thin skin, then popping the juicy flesh straight into my mouth—it’s such a satisfying treat.

Can dogs eat lychee?

I’ve read that dogs should avoid lychee because it can be too rich and potentially harmful for them.

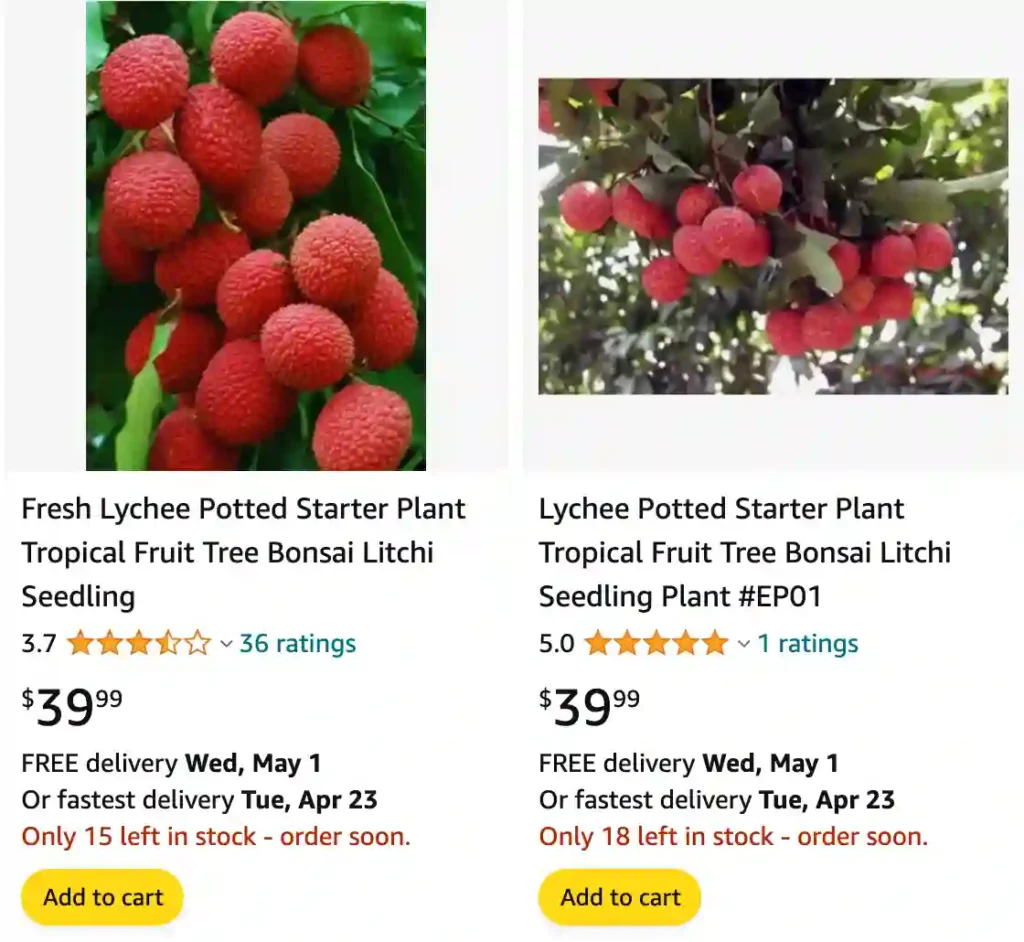

Where to buy lychee?

I find that the best places to buy lychee are Asian markets or specialty grocery stores, where it’s often fresher.

How to make lychee martini?

Making a lychee martini is a fun experience; blending lychee fruit with vodka and a touch of lime juice gives a delightful twist to a classic cocktail.

When is lychee season?

Lychee season is usually in the summer, and I always look forward to it because the fruit is at its peak then.

What does lychee smell like?

The smell of lychee reminds me of a floral garden; it’s light, sweet, and incredibly inviting.

How to tell if lychee is ripe?

I’ve learned that ripe lychee is slightly soft to the touch and has a fragrant aroma, so it’s easy to tell when it’s perfect to eat.

How to store lychee?

I keep lychee in the fridge to prolong its freshness, and it lasts a lot longer that way than if left at room temperature.

How to make lychee jelly?

Making lychee jelly is a fun kitchen project; mixing lychee juice with gelatin creates a deliciously wobbly treat that’s always a hit at gatherings.

Can cats eat lychee?

I’ve read that cats shouldn’t eat lychee either, as it can upset their stomach or cause other issues.

Can pregnant women eat lychee?

Pregnant women can enjoy lychee in moderation, but I always double-check with my doctor to make sure it’s safe for me.

Lychee vs Rambutan

I remember trying rambutan for the first time and being pleasantly surprised by its vibrant, hairy exterior and sweet, slightly tart flavor, which made me appreciate the lychee’s smoother, floral notes even more.

Lychee vs Longan

While enjoying a bowl of longan, I found its taste to be subtly sweet and less aromatic compared to lychee’s pronounced floral notes, which made me favor lychee for its more intense flavor and juiciness.

Lychee vs Chitubox

Comparing lychee to Chitubox was quite a leap—one is a tropical fruit bursting with juicy sweetness, while Chitubox is a software tool, so there’s really no taste comparison; however, I find myself enjoying lychee far more in my fruit bowl.

Lychee vs Litchi

I sometimes wonder about the difference between lychee and litchi since they seem to be the same fruit; but every time I eat them, I’m reminded that “lychee” is just the anglicized name for “litchi,” and I enjoy their sweet, floral taste either way.

Lychee vs Cura

I’ve found that lychee and Cura are worlds apart—lychee is all about the juicy, refreshing fruit, while Cura is a software that I use for 3D printing, so I’ll always pick lychee when I’m craving a delicious snack.

Lychee vs Dragon Fruit

Dragon fruit‘s vibrant look and mildly sweet flavor are striking, but I still find myself reaching for lychee more often due to its intense sweetness and juiciness that makes it a standout tropical treat.

Lychee vs Guinep

Guinep is interesting with its unique, tangy taste and challenging preparation, but I’ve found lychee’s easy-to-peel skin and sweet, succulent flesh to be far more satisfying when I’m in the mood for a tropical fruit.

Lychee vs Mangosteen

I absolutely love the creamy, rich flavor of mangosteen, but the crisp, sweet bite of lychee often wins me over when I’m looking for a refreshing fruit to enjoy on a hot day.

Lychee vs Photoprism

Just like Chitubox and Cura, Photoprism is another tech tool rather than a fruit, so there’s no comparison with lychee’s sweet, juicy appeal, which remains a favorite for me over tech solutions.

Lychee vs Piwigo

Piwigo, being a photo management software, has no taste to compare with lychee’s delicious, sweet flavor, making lychee an easy choice when I’m looking for a satisfying treat rather than a digital tool.

Lychee vs Quenepas

Quenepas, with its somewhat tangy taste and challenging texture, is intriguing, but lychee’s consistently sweet and juicy flavor keeps me coming back for more whenever I’m craving something fruity.

Lychee vs Strawberry

While strawberries are delicious with their bright, tart sweetness, I often find lychee’s unique, floral taste and juicy texture to be more refreshing and satisfying in a tropical fruit craving.

Lychee vs Tapioca

Tapioca, in its various forms, is versatile but lacks the immediate, refreshing sweetness of lychee, making lychee my go-to when I want a burst of tropical flavor rather than a starchy base for dishes.

The Lychee’s Ancient Legacy and Botanical Identity

Lychee is more than a simple fruit; it is a living artifact of history, steeped in myth, poetry, and the relentless pursuit of human desire. The fruit, with its vibrant red skin and translucent, sweet flesh, has captivated people for centuries, becoming a symbol of romance, luxury, and the enduring connection between a people and their native land. Its story begins not in a modern orchard, but in the annals of ancient China, where its exquisite taste set in motion epic journeys and inspired some of the greatest works of poetry.

The Storied Past: Lychee in Ancient China

The legacy of the lychee is most famously captured in a poem by the Tang dynasty poet Du Mu: “A steed which raised red dust won the fair mistress’ smiles, / No one knew it was for the litchi fruit it had brought”. This vivid imagery refers to the legendary horse-relay system established by Emperor Xuanzong to satisfy the cravings of his beloved concubine, Yang Guifei. Adored for her beauty and her love for the sweet lychee, Yang Guifei lived in the northern capital, Chang’an, while the fruit was grown nearly 1,900 kilometers away in the subtropical south, specifically in Guangdong province.

To bridge this vast distance and deliver the extremely perishable fruit while it was still fresh, the emperor repurposed a military and official communication network known as the Yizhan system. This network, one of the world’s earliest large-scale logistics operations, employed relay riders on fast horses to transport the precious cargo day and night, switching out at stations along the way to maintain a breakneck pace of more than 500

li (approximately 160 kilometers) per day. The journey was so demanding that historical accounts note many couriers died along the way, a testament to the fruit’s immense value and the emperor’s boundless affection. Ancient methods were also employed to preserve the lychees, such as sealing them in empty bamboo tubes to limit oxygen exposure and slow down the fruit’s metabolism. This legendary tale of imperial desire underscores a fundamental truth about the lychee: its delicate nature and rapid deterioration after harvest are central to its mystique and value.

The history of lychee cultivation extends even further back, with records dating the practice for over 2,000 years in southern China, specifically in the Kwangtung and Fukien provinces. A royal record from 111 BC during the Han dynasty describes Emperor Hanwu’s failed attempt to plant lychee trees in his palace, a detail that highlights the plant’s specific and non-negotiable climatic needs. It requires a distinct subtropical environment, one that provides cool, non-freezing winters to stimulate flowering. This botanical requirement explains why its cultivation took firm root in the south but was impossible in the colder northern climate. The Chinese people’s enduring passion for the fruit is further demonstrated by the rich diversity of cultivars mentioned in imperial documents during the Song dynasty, which listed 32 varieties in Fujian province alone by 1059 AD. One such cultivar, the “Hanging Green,” was so rare and revered that it was a long-standing item of tribute to the imperial government, until a local revolt led to the felling of all but one tree.

The Botanical Profile of Litchi chinensis

The lychee tree’s botanical identity is as unique as its history. Scientifically classified as Litchi chinensis Sonn., it is the sole member of its genus and belongs to the larger soapberry family, Sapindaceae. This family also includes its notable cousins, the longan and rambutan. The species name,

chinensis, is a direct reference to its primary origin in China, a detail that has been internationally recognized since the 19th century when foreign botanists began to study the plant. While its cultural roots are firmly in China, its native range also extends to northern Vietnam and parts of Malaysia, where wild trees can still be found in elevated rainforests.

The lychee’s journey from its native habitat to the global stage was a slow process, constrained by its exacting climatic requirements and the short viability of its seeds. Over centuries, it spread from China to Burma in the 17th century, India a hundred years later, and then to Madagascar and Mauritius in the 1870s. It arrived in Hawaii in 1873, Florida in 1883, and California in 1897, brought by Chinese traders, missionaries, and emigrants who carried the seeds with them. Today, while it is cultivated in subtropical regions around the world, the greatest diversity of varieties remains in its ancestral home of Southeast Asia.

As a plant, the lychee is a broadleaf evergreen with a dense, rounded canopy that can reach a height of 20 to 30 feet in cultivation, though it can grow up to 110 feet in its native habitat. Its leaves are particularly handsome, with a glossy, dark green hue and a pinnate compound structure, each consisting of 4-8 lanceolate leaflets. One of the tree’s most striking aesthetic features is the color of its new growth, which emerges a beautiful bronze-red before maturing into its characteristic dark green. This constant cycle of new, colorful flushes adds to its value as a landscape tree, providing both shade and botanical interest.

A Time Lapse of Growth — My Lychee Tree Journal

The journey of a lychee tree is a masterclass in patience. It is a story of slow, deliberate growth, where a single, fleeting moment of fruit can be the culmination of years of dedicated care. As a gardener, I’ve come to understand that cultivating a lychee from a seed is an act of faith, a commitment to a long-term relationship with a plant that will test your patience and, eventually, reward you with a taste of its ancient legacy. This chronicle is a record of that journey, from a simple seed to a towering, fruit-bearing tree.

Entry 1: A Seed’s Promise (Month 1-3)

The decision to grow a lychee from a seed was a philosophical one. I knew from my reading that an air-layered tree would produce fruit in 3 to 5 years, while a seed-grown tree could take 10 to 15 years. But there was something deeply appealing about starting a life from its absolute beginning, of witnessing the slow, organic unfolding of its genetic potential. I carefully selected a large, healthy-looking fruit, enjoyed its sweet flesh, and extracted the plump, shiny brown seed. My first step was to place the seed in a glass of water, changing it daily, a simple act of nurture that felt like a quiet conversation with the life within. I had also read that the seed could be germinated using the paper-towel method, which involves placing it in a moist paper towel inside a ziplock bag. I chose the glass of water method, but it was reassuring to know there were multiple paths to the same beginning.

Within a week, the seed had begun to swell and a tiny root emerged. The germination was surprisingly fast, taking only about ten days. This quick start was a stark contrast to the long road ahead. I planted the young seedling in a medium-sized pot with a drainage layer at the bottom, using a well-draining, slightly acidic soil. The initial growth was, as the literature had suggested, rapid and vigorous. The first set of new leaves emerged, a beautiful bronze-red hue, unfurling like tiny, delicate flags. This first flush of growth was a visual spectacle, a burst of energy that belied the slow, deliberate pace the tree would soon adopt.

Entry 2: The Eager Green Years (Years 1-4)

The next several years were a lesson in patience. The young tree, though growing, was still in its juvenile phase, a period of dedicating all its energy to developing a strong root system and a solid framework of branches. I understood that this was the most critical time for establishing the tree’s architecture and health, which would directly impact its future as a fruit-bearer.

My management during this time was driven by a single principle: providing the right conditions without overdoing it. I followed a strict fertilization schedule, applying a complete fertilizer every eight weeks. The ideal mix, I learned, contained 6-8% nitrogen, 2-4% available phosphorus, and 6-8% potash, along with essential micronutrients like magnesium, manganese, zinc, and iron. This balanced diet was crucial for the tree’s health, and I made sure to use foliar applications of manganese and zinc, as recommended for trees in high-pH, calcareous soils. The soil was consistently maintained with a slightly acidic pH and good drainage, a non-negotiable requirement for lychee.

Pruning was also a regular, intentional practice. After each vegetative flush, I would lightly prune the branches, a technique that guides the tree’s shape and encourages a stronger, more compact canopy. I covered the fresh cuts with latex paint to protect against pests. This regular shaping was in direct contrast to the heavy pruning needed for rejuvenation, which would only be performed on old or truly immature trees. The goal was to build a solid foundation, a strong frame that could one day support the weight of a bountiful harvest. My tree grew slowly but steadily, its glossy green leaves a constant source of quiet joy, as I waited for the day it would show its first sign of maturity.

Entry 3: The Cold Kiss of Winter (Year 5)

The turning point came in the fifth year. I had read about the lychee’s critical need for a period of cool, dry weather to trigger flowering, a phenomenon often measured in “chilling hours”. The winter was cooler than usual, with daytime temperatures below 68°F and nighttime lows not dipping below freezing. I also followed the advice of withholding water from the mature tree during this time, creating a mild drought stress to further enhance the flowering potential.

The tension in the air was palpable; I was actively manipulating the tree’s environment, hoping for a specific biological response. The tree’s quiet dormancy in winter was not a period of rest but a crucial, almost magical, time of internal transformation. And then, it happened. In late winter, instead of the familiar bronze-red flush of new leaves, the tree began to produce long, drooping panicles of small, greenish-yellow flowers. This was it—the culmination of five years of careful tending. The tree had shifted its energy from vegetative growth to reproductive growth, a direct consequence of the cool, dry weather. This moment was the true beginning of its adult life.

Entry 4: The Fruits of Labor (Summer of Year 5)

The flowering was prolific, though I knew from my research that only a small fraction of the flowers would actually be pollinated and set fruit. I watched as the flowers gave way to tiny green globes. This period, known as the fruit development stage, was characterized by the rapid growth of the embryo and the development of the aril, the juicy pulp that surrounds the seed.

The most spectacular change came as the fruit matured. The small, warty skin, initially green, began a slow transformation. I watched as the chlorophyll degraded and the fruit synthesized anthocyanins, a process that painted the skin in vibrant shades of pink and red. Within a few weeks, the tree was laden with beautiful, strawberry-red clusters of fruit, turning it into a truly decorative and breathtaking specimen. I could see the subtle differences between each fruit, a result of the unique genetic makeup of a seed-grown tree. The fruit’s skin became brittle and easy to peel, revealing the translucent white flesh within.

Entry 5: Harvest and Renewal (Post-Harvest)

The day of the first harvest was a moment of profound satisfaction. I broke open a fruit, its delicate, floral aroma filling the air. The flesh was firm, juicy, and intensely sweet, a flavor often compared to rose water or a combination of pear and grape. It was the taste of five years of patience, of careful tending, of a deep and respectful connection with a plant.

But the journey wasn’t over. I immediately understood the importance of the next step: post-harvest pruning. I carefully trimmed the branches, removing about 4 inches of the fruited stems. This practice is not just about shaping the tree; it is a crucial part of the life cycle. Pruning after harvest stimulates the growth of new shoots and leaves before the weather cools down, allowing the tree to prepare for its next dormant period and, with any luck, its next round of flowering and fruiting. The harvest was the end of one chapter, but the pruning was the intentional beginning of the next, a testament to the continuous, time-lapse nature of a lychee’s life.

The Definitive Guide to Lychee Cultivation

The personal journey described in the previous section is a testament to the enduring principles of lychee cultivation. This detailed guide provides the technical and practical information necessary to successfully grow a lychee tree, whether for personal enjoyment or commercial production.

Selecting the Right Lychee Cultivar

One of the most critical decisions for any aspiring lychee grower is the choice of cultivar. Different varieties offer unique flavor profiles, fruit sizes, and, most importantly, varying levels of climate tolerance and consistent production. The selection dictates the entire growing experience and the quality of the final harvest.

- ‘Mauritius’: This is a cherished traditional variety, often recommended for warmer, subtropical areas as it requires less chilling to bear fruit consistently. It is favored by many for its balanced flavor, which offers a hint of acidity alongside its sweetness, giving it a richer, more complex character. It is also known for a pleasant “rose water” quality in its flavor and for being a reliable bearer.

- ‘Sweetheart’: As its name suggests, this cultivar is celebrated for its intensely sweet, less tart flavor profile. Its fruit is often heart-shaped and it is a self-pollinating variety, making it a wonderful choice for home gardeners.

- ‘Brewster’: This variety is highly regarded by many lychee connoisseurs for its strong, wonderful “lychee/rose scent” and flavor. It is known for its sweet flesh, but is often criticized for having a larger seed. While its flavor is often considered superior, it can be less consistent in its fruiting compared to other varieties.

- ‘Haak Yip’: This cultivar is prized for its prolific fruiting and superior quality fruit. Its fruit is medium to large, with a deep red, slightly rough skin, and a small seed. It is a self-fertile variety with a sweet, aromatic flavor balanced by a hint of tartness, making it excellent for fresh eating and culinary use.

The table below provides a concise, at-a-glance comparison of these popular varieties, a vital tool for making an informed decision.

Table: Comparison of Popular Lychee Cultivars

| Cultivar Name | Appearance (Fruit Skin) | Flavor Profile | Key Characteristics | Best Climate |

| Mauritius | Rough, pinkish-green to red | Sweet with a balanced tartness; floral | Reliable bearer; rich, complex flavor | Warmer subtropical climates |

| Sweetheart | Vibrant red, heart-shaped | Intensely sweet, low tartness | Self-pollinating; high sugar content | USDA Zones 9-11 |

| Brewster | Red, with a large seed | Intense lychee/rose flavor and scent | Highly-prized flavor; less consistent fruiting | Areas with sufficient chilling |

| Haak Yip | Deep red, slightly rough | Sweet, aromatic, with a hint of tartness | Prolific fruiting; small seed size | Subtropical/Tropical |

Creating the Optimal Growing Environment

Successful lychee cultivation is not about luck; it is a direct result of carefully managing the tree’s environment to match its specific needs. The lychee is a subtropical plant, and its requirements are non-negotiable.

- Climate and Hardiness: The lychee thrives in USDA Hardiness Zones 10-11, where it is a broadleaf evergreen. A crucial requirement for mature, fruit-bearing trees is a cool, dry winter period to trigger flowering. Temperatures must drop below 68°F but remain above freezing for three to five months to achieve the necessary “chilling hours”. Without this cool period, the tree will not transition from vegetative to reproductive growth and will fail to flower.

- Soil and Site Selection: Lychee trees prefer acidic, well-drained soils, with a pH of 5.0 to 5.5 being ideal. They perform best in sandy loams with a moderate organic matter content. The tree should be planted in a location that receives full sun and is protected from strong winds, as its dense canopy makes it susceptible to wind damage. Planting on a mound of soil can also prevent water from pooling around the trunk, which lychees dislike.

- Watering and Irrigation: A dual watering strategy is essential for a healthy tree. Young, newly planted trees require regular irrigation to help them establish and grow. However, for mature trees that are four or more years old, a period of mild drought stress in the fall and early winter (September or October) can significantly enhance flowering in the spring. Once flowering begins, and especially during fruit development, regular irrigation should be resumed.

A key point that distinguishes expert cultivation from amateur gardening is the understanding of the plant’s growth cycles and how to influence them. The research indicates that for mature trees, applications of nitrogen-containing fertilizer should be avoided from August until early spring. This is a critical causal relationship. The application of nitrogen during this period can stimulate new vegetative growth (shoots and leaves), which can entirely suppress the floral flush and eliminate the potential for fruit production. Therefore, a grower must actively manage their fertilization and watering schedules to guide the tree toward its flowering stage, rather than just letting it grow on its own.

Propagation: From Seed to Air-Layering

Lychee trees can be propagated in several ways, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

- Growing from Seed: This method is the simplest to start, but it requires significant patience. Lychee seeds germinate quickly, often within ten days, but a tree grown from seed can take 10 to 15 years to produce fruit. This method also does not guarantee that the new tree will have the same characteristics as its parent, as genetic variation can occur.

- Air-Layering: This is the most common commercial method for propagating lychee trees, and for good reason. An air-layered tree is, in essence, a clone of the parent tree, guaranteeing the specific cultivar traits and significantly shortening the time to fruit production to just 3 to 5 years. The process involves creating a new, mature tree from a branch while it is still attached to the parent plant.

Step-by-Step Guide to Air-Layering

- Select a Branch: Choose a healthy, young branch that is approximately 1/2 to 1 inch in diameter, ideally one that bifurcates or trifurcates, to create a well-proportioned new tree.

- Remove Bark and Cambium: Using a sharp knife, carefully remove a complete, circular section of bark about 1 inch wide from the branch. The vascular layer just beneath the bark, known as the cambium, must also be scraped away to prevent the wound from healing.

- Apply Rooting Hormone (Optional): While not strictly necessary, a rooting hormone such as indole-acetic acid can be brushed onto the exposed area to encourage root development. Care must be taken to not use excessive amounts, as this can have a suppressive effect.

- Wrap with Moist Growing Medium: Soak sphagnum moss or another loose, well-drained medium and squeeze out the excess water. Wrap a large handful of the moist medium tightly around the exposed wound on the branch.

- Seal for Moisture and Protection: Cover the moss and wound with a sheet of clear plastic or heavy-duty aluminum foil to hold in moisture. Securing the ends with twist ties or duct tape will create a sealed environment and prevent pests like ants from entering.

- Wait and Watch: After several weeks, typically 8 to 12 weeks, roots will begin to form. If using clear plastic, the roots will be visible; if using foil, the readiness is indicated when the foil-wrapped ball feels tight and firm.

- Cut and Pot: Once a sufficient root ball has developed, the branch should be cut from the parent tree, about 1 to 2 inches below the root mass. After removing the wrapping, at least 50% of the foliage should be pruned away to reduce water loss while the new tree establishes itself. The root ball should be soaked in water until fully saturated before planting in a pot or directly in the ground.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Lychee trees are generally resilient, but they are susceptible to a range of pests and diseases, many of which can be managed with proactive cultural practices and timely intervention. The most successful approach to managing these issues is not simply reacting to problems as they arise, but by understanding the conditions that allow them to flourish and preventing them in the first place.

Pest Management: A Proactive Approach

- Lychee Erinose Mite (LEM): This mite, which is becoming increasingly common in lychee growing areas, specifically attacks new growth, including leaves, flowers, and fruits. It can be spread by wind, insects, and even on tools and clothing. The most effective management strategy is a multi-step process that combines cultural and chemical controls. First, any infested plant parts should be pruned and immediately destroyed, either by chipping or by sealing the material in bags and exposing them to sunlight for at least three days to solarize and kill the mites. Next, all tools and equipment must be washed with a 10% bleach solution to prevent the mite from spreading to other trees. Finally, sulfur, specifically a product like Microthiol Disperss, should be applied to protect the new leaf flush as it emerges. Applications should be repeated every 7 to 15 days from bud break until all leaves have hardened. It is important to avoid applying sulfur with oil or when temperatures are above 90°F.

- Scales: Pests like plumose (Morganela longispina) and Philephedra tuberculosa scales can attack stems, and heavy infestations can lead to stem dieback. These insects are often kept in check by natural predators, but if populations get out of control, treatment may be necessary. The most effective control is achieved when the scales are in their nymphal stages, as eggs and adults are more resistant to insecticide applications.

- Root Weevils: Adult Diaprepes root weevils (Diaprepes abbreviatus) and citrus root weevils feed on lychee leaves, causing minor, cosmetic notching damage. However, the real threat comes from their larvae, which feed on the roots, leading to a loss of tree vigor and providing entry points for fungal infections. Management often involves cultural practices that improve tree health and vigor to help it withstand the damage.

Disease Prevention and Treatment

- Root Rot and Tree Decline: Many forms of root rot and tree decline are a direct consequence of a poor growing environment. The primary cause of this disease is poorly drained or overwatered soil, which creates anaerobic conditions where roots cannot get the oxygen they need to survive. The dying roots then become susceptible to dormant soil fungi, such as Pythium, Phytophthora, or Fusarium, which can further spread the decay. To prevent this, the single most important action is to ensure the tree is planted in well-drained soil and to avoid overwatering. Improving the soil with organic manure can also enhance its biological resilience. If a tree is moderately affected, pruning out the infected roots can sometimes save it, but severely infected trees should be removed to prevent the disease from spreading.

- Anthracnose: This is the major disease that attacks lychee fruit. Symptoms include irregularly shaped tan to dark brown spots on the leaves and, more seriously, post-harvest decay and browning of the fruit. The fungus thrives in conditions of high humidity, continuous rain, and high temperatures. Management strategies focus on reducing the conditions that promote the disease: pruning the canopy to improve air circulation and light penetration, and removing and destroying fallen leaves and infected branches from the orchard. Copper-based fungicides can be effective for initial outbreaks, but “calendar sprays” close to harvest are not recommended as they can lead to unacceptable residues.

A thorough examination of the challenges faced by lychee trees reveals a consistent pattern: many of the most serious problems are not isolated attacks by a singular pest or disease, but rather a culmination of improper cultural practices. For example, root rot is not just caused by a fungus, but by overwatering and poor drainage which create the ideal conditions for that fungus to attack. Similarly, anthracnose is exacerbated by a dense, poorly ventilated canopy. Therefore, the most effective and sustainable approach to managing lychee tree health is to focus on preventative care and good horticultural practices—such as proper soil drainage, strategic watering, and regular pruning—to create an environment where these pests and diseases cannot thrive.

The Three Cousins: Lychee vs. Longan vs. Rambutan

Lychee is often compared to its close relatives, longan and rambutan, a trio of tropical fruits that share a similar genetic heritage and are all members of the Sapindaceae family. While they may appear and taste similar to the uninitiated, each fruit possesses its own unique characteristics, from its external appearance to its nutritional composition and health benefits.

Anatomy of the Soapberry Family

The most obvious difference between the three fruits is their appearance. Lychee has a bumpy, “leather-like” pericarp that is typically pink or red when ripe. Rambutan is the largest of the three, about the size of a golf ball, and is instantly recognizable by its vibrant red skin covered in “long, soft spines”. Longan is the smallest, with a smoother, light brown, and leathery skin.

Once peeled, however, the fruits all reveal a similar-looking, translucent white flesh surrounding a large, shiny black seed, a clear sign of their close relationship. Their flavors, though, are distinct. Lychee is generally considered the sweetest and most fragrant, with a floral taste that is often compared to rose water. Rambutan also has a sweet and flowery flavor with a creamy texture. Longan, on the other hand, is noted for its “more tart, musky flavor” with a honey-like undertone, making it the most distinct of the three.

A Nutritional and Health Showdown

While all three are low-calorie, low-fat fruits rich in Vitamin C, a detailed nutritional analysis reveals key differences that contribute to their unique health impacts.

- Lychee: This fruit contains the highest amount of sugar among the three, with 15.2 grams per 100g. Its top mineral is copper, which covers 50% of the daily recommended value per 100g and plays a vital role in building bones, skin, and hair. Lychee also contains vitamins K and E, which are not found in longan or rambutan. Furthermore, extracts from lychee have been shown to have significant anticancer effects, with proven efficacy against liver cancer cells. Lychee is a low-glycemic index food, with a GI of 48.

- Longan: This fruit is the winner in both Vitamin C and potassium content, providing 84mg of Vitamin C per 100g, which is nearly the full daily recommended value. A key distinguishing feature of longan is its “nootropic effect,” which means it can improve memory and cognitive functions. It also has anxiolytic properties that can fight anxiety and stress, leading to improved sleep. Like lychee, longan is a low-glycemic index food, with a GI of 45.

- Rambutan: Rambutan has the highest carbohydrate content, providing 20.9 grams of carbs per 100g, and is also the highest in calories at 82 calories per 100g. Its top minerals are manganese and iron, and it contains the highest amount of Vitamin B3. Extracts from rambutan seeds have also shown potential anticancer effects by inhibiting the growth of cancer cells. Due to its high carbohydrate content, rambutan has a medium glycemic index of 59.

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of these three fruits, summarizing their key differences for easy reference.

Table: Lychee vs. Longan vs. Rambutan

| Feature | Lychee (Litchi chinensis) | Longan (Dimocarpus longan) | Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) |

| Appearance (Skin) | Bumpy, leathery, pink to red | Smooth, light brown, and thin | Hairy, red, with soft spines |

| Taste Profile | Sweetest, most fragrant, floral | Tart, musky, honey-like undertone | Sweet, flowery, creamy texture |

| Key Nutritional Highlight | Highest in copper and sugars | Highest in Vitamin C and potassium | Highest in carbs, manganese, and iron |

| Key Health Impact | Anticancer (liver cancer), promotes collagen | Nootropic (memory), anxiolytic (sleep) | Anticancer (seed extract), rich in B3 |

| Glycemic Index | 48 (Low) | 45 (Low) | 59 (Medium) |

| Serving Size | 190g (1 cup) | 3.2g (1 fruit) | 214g (1 cup) |

Culinary and Traditional Uses

Beyond being eaten fresh, the lychee is a highly versatile ingredient in various cuisines. Its sweet, fragrant, and floral flavor profile makes it a popular addition to desserts, such as sorbets, ice creams, and cakes. It also works beautifully in savory dishes, adding a refreshing twist to stir-fries, salads, and even as a glaze for meats. The fruit’s flavor pairs exceptionally well with other ingredients like ginger, coconut, lime, and mint. Lychee can also be used as a base for smoothies, cocktails, and mocktails, providing a tropical flair to beverages.

In traditional Chinese medicine, lychee has been used for centuries to treat a wide range of ailments, including stomach ulcers, diabetes, and coughs. Its health benefits have been attributed to its high content of polysaccharides and polyphenols, which have been proven to possess antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and immunomodulatory properties. This long history of medicinal use further solidifies the lychee’s role as not just a delightful fruit, but a potent natural remedy in the cultures that have cherished it for millennia.

If i die, water my plants!