I. Introduction: Unveiling the Elephant Ear Staghorn Fern

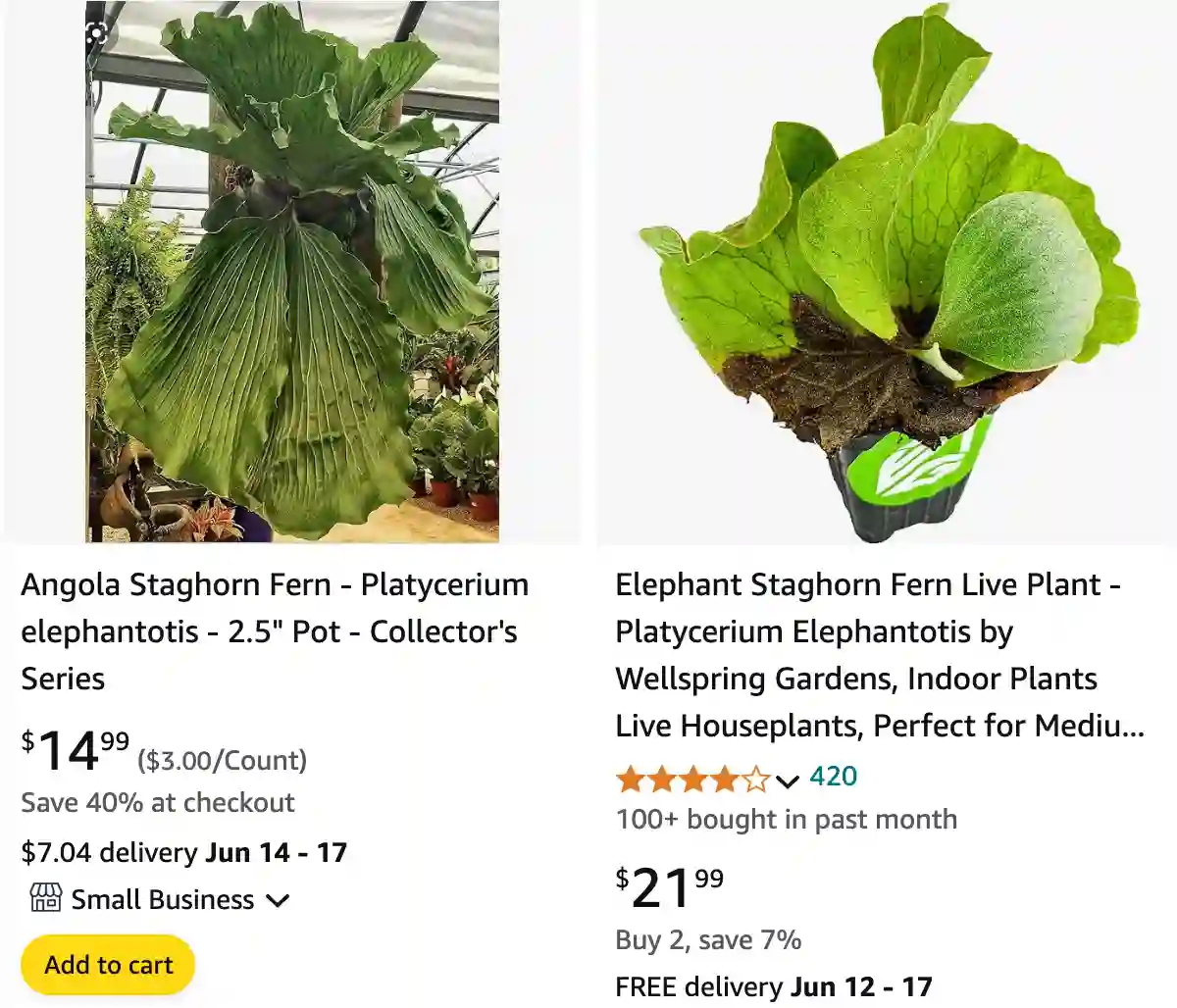

The botanical world is replete with wonders, but few plants capture the imagination quite like the Platycerium elephantotis, commonly known as the Elephant Ear Staghorn Fern. This captivating epiphyte stands out with its distinctive, large, unforked, and rounded fronds that truly resemble the ears of an elephant, a characteristic that sets it apart from many of its antler-shaped relatives within the Platycerium genus. Native to the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, with a wide distribution across countries like Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria, this fern naturally thrives by attaching itself to trees rather than growing in soil. Its unique morphology and epiphytic lifestyle make it a popular and striking ornamental plant, often cultivated as a houseplant to bring a touch of the rainforest indoors.

What truly distinguishes Platycerium elephantotis within its genus is not just its unique frond shape, but also its impressive size potential and remarkable longevity. While many Platycerium species are known for their deer or elk antler-like fronds, P. elephantotis boasts broad, rounded foliage that can reach an overall height of six feet and produce mature shield leaves over 2.5 feet across in cultivation. In ideal environments, its leaves can even extend to an astonishing 8-10 feet long. Beyond its visual grandeur, this fern is a testament to endurance, often living for decades, with some well-cared-for specimens thriving for 80 to 90 years.

Despite its majestic appearance and long life, Platycerium elephantotis sometimes carries a reputation for being challenging to cultivate. However, this perception can be misleading. Experienced growers often clarify that this fern is not inherently difficult but rather possesses a very specific and non-negotiable requirement for consistent moisture. Unlike many other staghorn fern species that prefer to dry out between waterings,

P. elephantotis thrives when its growing medium is kept evenly moist and should never be allowed to completely desiccate. This particular hydration need is the primary “trick” to its successful cultivation. When gardeners apply general staghorn fern care practices, which often involve allowing the plant to dry out, they inadvertently create conditions detrimental to

P. elephantotis. Therefore, understanding and consistently meeting this unique moisture demand transforms the plant from a perceived challenge into a manageable and highly rewarding botanical companion.

II. Botanical Profile: Anatomy of an Epiphytic Marvel

Scientific Classification and Kinship within Platycerium

Platycerium is a fascinating genus comprising approximately 17 to 18 accepted fern species, all members of the Polypodiaceae family. These ferns are widely recognized by their common names, “staghorn fern” or “elkhorn fern,” due to the distinctive, often forked or antler-like shapes of their fronds.

Platycerium elephantotis, also known by its synonym P. angolense, is a prominent member of this genus. Its natural range spans tropical Africa, encompassing a vast distribution across countries such as Angola, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Interestingly, it has also been introduced and established in the northwest regions of South America. Among the cultivated

Platycerium species, P. elephantotis stands out as one of the larger varieties, contributing significantly to its imposing presence.

Native Habitat and Ecological Role

The natural habitat of Platycerium ferns, including P. elephantotis, is the humid, dappled light environment of tropical and subtropical rainforests. Here, they exhibit an epiphytic growth habit, meaning they grow on other plants, primarily in the branches and trunks of trees, rather than rooting in the soil. This aerial existence necessitates unique adaptations for nutrient and water acquisition. These ferns absorb moisture and essential nutrients directly from the air, from rainwater, and from organic debris that collects in the crooks of tree branches where they reside.

A remarkable aspect of their ecological role is the function of their specialized fronds in creating a self-sustaining nutritional system. The basal fronds, often referred to as shield fronds, are designed to laminate against the tree trunk, forming a protective barrier for the fern’s root structure. Over many years, these shield fronds actively collect falling forest litter, rainwater, and even animal droppings, building up their own “compost” system. This ingenious mechanism allows the fern to recycle organic matter into a rich, long-term source of nutrition and moisture. This highly evolved strategy underscores the plant’s profound adaptation to its epiphytic lifestyle, transforming environmental detritus into vital sustenance. It is a testament to nature’s efficiency, where the plant doesn’t merely exist on a host but actively cultivates its own nutrient base.

Distinctive Morphology: Shield Fronds vs. Fertile Fronds

Platycerium elephantotis, like other members of its genus, exhibits dimorphism in its fronds, meaning it produces two distinct types of leaves, each with specialized functions.

- Basal/Shield Fronds (Sterile): These fronds are broad, shield- or kidney-shaped, and sterile, meaning they do not produce spores. For P. elephantotis, these are characteristically tall and arched. Their primary role is to laminate tightly against the mounting surface (e.g., a tree trunk or mounting board), effectively covering and protecting the fern’s root structure from damage and desiccation. Beyond protection, these fronds are crucial for the fern’s nutrition. They are designed to collect and trap falling organic debris, such as leaves, bark, and even animal droppings, which decompose over time to form a rich, self-made compost system that feeds the plant. As part of their natural lifecycle, these shield fronds will eventually turn brown and dry up. It is imperative not to remove these seemingly “dead” fronds, as they continue to provide vital structural support, absorb excess moisture, and release stored nutrients to the fern, contributing significantly to its overall health and longevity.

- Fertile Fronds: These are the showy, green fronds responsible for reproduction, bearing spore patches on their undersurface. In the case of Platycerium elephantotis, these fronds are truly unique within the genus. Unlike the typical antler-like or bifurcated (forked) fronds of many other Platycerium species, P. elephantotis fertile fronds are distinctly large, broad, rounded, and notably unforked, giving them their common “elephant ear” appearance. They feature a distinctly veined surface and typically bear a single, large, round spore patch located at their base.

Growth Habits and Mature Dimensions

Platycerium elephantotis is known for its robust growth, capable of reaching impressive dimensions over time. In cultivation, it can achieve an overall height of six feet, with its mature shield leaves spanning over 2.5 feet across. The fertile fronds typically grow to 24-30 inches in length, while the sterile (shield) fronds measure 18-24 inches. Under optimal conditions, some reports indicate leaves can grow even larger, reaching lengths of 8-10 feet.

The growth of P. elephantotis is markedly seasonal. During the spring, the previous year’s shield fronds naturally die back, making way for new shield fronds that begin to form during the summer months. Following the development of these new shield fronds, fresh fertile fronds emerge and continue to grow. Horticultural experts sometimes suggest trimming back the tops of the shield fronds to encourage a more erect growth habit. This fern is also a remarkably long-lived plant; with appropriate care, it can thrive for many decades, often exceeding 50 years, and some documented specimens have flourished for 80 to 90 years. This longevity makes it a truly enduring botanical centerpiece.

III. The Gardener’s Time-Lapse: My Journey with the Elephant Ear Fern

Chapter 1: The Seed of a Dream (Months 1-3)

My journey with the magnificent Elephant Ear Staghorn Fern began not with a grand, established specimen, but with a humble beginning. I remember the excitement of preparing its first home, knowing I was embarking on a long-term relationship with this unique epiphyte. For many, the simplest way to start is by acquiring a small baby staghorn from a nursery. However, for those seeking a more profound connection to the plant’s life cycle, propagation from spores or by dividing pups offers a truly immersive experience.

Spore Propagation: A Detailed Beginning To propagate from spores, one must first collect them. I gently scraped the tiny, brown dots from the underside of a mature fertile frond onto a piece of white paper. These spores are essentially single cells, often equipped with a sticky substance that helps them adhere to surfaces. After collection, I lightly tapped the paper to separate the minute spore casings from the actual spores.

The next critical step involves preparing a sterile growing environment. I used a plastic container with a tight-fitting lid, layering 1-2 inches of fine perlite at the bottom, followed by 2-3 inches of peat moss. Coconut coir is also an excellent alternative. It’s crucial that this medium is completely drenched with water but not waterlogged, maintaining a crumbly texture. Some growers even suggest adding a tiny amount of fertilizer at this initial stage. To ensure sterility, I microwaved the covered container for ten minutes. Once cooled, I added more distilled water or reverse osmosis (RO) water. Finally, I carefully sprinkled the collected spores evenly over the moist medium. The container was then sealed, creating a mini-atmosphere where condensation would form and “rain” down on the spores, a vital step for their development. This propagator was placed in a cool, dimly lit spot, away from direct sunlight.

The waiting game then began. Spore germination typically occurs within 7 to 14 days after sowing. Over the next few weeks to several months, these single cells develop into prothallia, which appear as a thin, green mat on the growing medium. The male and hermaphroditic gametophytes, the sexual stages of the fern, reach maturity remarkably quickly, often within 10 to 12 days. Fertilization then takes place, leading to the development of the sporophyte, the true fern plant. Tiny sporophytes, or baby ferns, usually become visible about a week after fertilization. While the entire process from spore to a sizable, mature fern can take a considerable 5 to 10 years , it’s important to note that

P. elephantotis is reportedly challenging to grow from spores, with successful sporelings sometimes appearing spontaneously under ideal conditions rather than through deliberate cultivation.

Pup Division: A Quicker Path For a more immediate and generally easier propagation method, dividing pups is highly effective. I carefully inspected my mature plant for healthy offshoots, or “pups,” that had developed their own distinct roots and fronds. Springtime is often considered an optimal period for this procedure. Using a sharp, sterilized knife or scissors, I gently severed the selected pup from the parent plant, ensuring a clean cut to minimize stress on both.

Once separated, the pup’s roots were carefully wrapped in a moisture-retentive medium like sphagnum moss or coconut coir. The wrapped pup was then mounted onto a piece of wood, a board, or placed in a pot filled with a well-draining, soilless medium such as peat moss. Crucially, maintaining high humidity and warmth is essential to encourage successful rooting for these newly separated plants. A light initial watering helps settle the medium around the roots.

P. elephantotis is known to produce pups freely when grown in warm, bright conditions , making division a reliable method for expanding one’s collection or sharing with fellow enthusiasts.

Chapter 2: Rooting and Reaching (Months 3-12)

As my young fern began to establish, whether from a tiny sporeling or a newly mounted pup, my focus shifted to providing the perfect environment for its continued development. Mounting it felt like bringing a piece of the rainforest canopy into my home, a true mimicry of its natural habitat. I learned to read its subtle cues, adjusting light and moisture to ensure its thriving.

Mounting and Substrate: Platycerium elephantotis truly flourishes when mounted, replicating its natural epiphytic growth habit on tree trunks in the wild. Common mounting options include wood plaques, boards, or even directly onto logs or trees in suitable climates. The chosen substrate is critical: sphagnum moss or other moisture-retentive, yet well-draining, media are ideal. Coconut coir or pure peat moss also serve as excellent choices. To secure the fern to its mount, I used twine or clear fishing line, ensuring that the delicate reproductive fronds were not constricted. Over time, the basal fronds will grow to envelop and conceal the securing material. For those opting for a pot, a well-draining potting mix, or a blend of sphagnum moss, pine bark, cactus soil, or sand, is recommended to provide the necessary aeration and drainage.

Light Requirements: This fern thrives in bright, indirect light, mirroring the dappled sunlight it receives beneath the rainforest canopy. It is crucial to shield it from harsh, direct sunlight, which can easily scorch its sensitive fronds. An ideal exposure provides 4-6 hours of medium to bright indirect light daily. Insufficient light, conversely, can hinder growth and even predispose the plant to fungal diseases.

P. elephantotis is often described as shade-loving, preferring filtered shade conditions.

Temperature and Humidity Needs: As a tropical native, P. elephantotis prefers warm, consistent temperatures. The ideal range is typically 60-80°F (16-27°C) , though it can tolerate a broader spectrum of 40-100°F (4-38°C). Protection from frost is paramount; temperatures dropping below 40-55°F will cause damage or even shock and death, necessitating bringing outdoor plants indoors during colder periods. High humidity is perhaps the single most critical environmental factor for this fern’s well-being. An ambient humidity level of around 70% is considered ideal. Regular misting, especially in dry indoor environments, or placing the plant in a naturally humid area like a bathroom, or utilizing a humidifier, greatly contributes to its health. Care should be taken to avoid leaving standing water droplets on the fronds themselves, as this can encourage rot.

Initial Watering and Fertilization: One of the most crucial lessons I learned was Platycerium elephantotis‘s distinct watering preference. Unlike many other staghorn ferns that appreciate drying out between waterings, this species demands consistent moisture and should never be allowed to completely dry out. This is a key differentiator in its care. During its active growing season, watering twice a week is often recommended. The most effective method for mounted ferns is to submerge the entire root ball and mount into a bucket or sink filled with water for several minutes until saturated. After soaking, allow the plant to drip dry thoroughly before re-hanging. It is generally advised to avoid watering the roots directly with a watering can, as this can lead to root rot.

For fertilization, a diluted, balanced liquid fertilizer is best. I opted for a half-strength orchid fertilizer, but a 1:1:1 organic (like fish emulsion) or 8:8:8 chemical fertilizer also works well. Young plants benefit from monthly feeding during their active spring and summer growth, reducing to bi-monthly during dormancy. Established plants may only require one or two feeds per growing season. Some growers prefer slow-release granular fertilizers tucked around the basal fronds. A common misconception is that banana peels serve as good fertilizer; however, these often attract pests and offer minimal nutritional benefit to the fern.

Chapter 3: Flourishing Fronds (Years 1-3)

The first year brought remarkable changes, transforming my young Platycerium elephantotis from a delicate start into a burgeoning display of botanical artistry. The fronds unfurled, growing larger and more defined, truly beginning to resemble the majestic “elephant ears” I had envisioned. I noticed the subtle seasonal rhythm of its growth, the browning of old shield fronds gracefully making way for new, vibrant green foliage.

Detailed Care Guide: My care routine solidified during this period, focusing on consistency. I continued the specific watering regimen, ensuring the plant remained evenly moist without being waterlogged, adjusting the frequency slightly based on ambient temperature and humidity. Regular misting remained a daily ritual, especially during drier periods, to maintain the high humidity this tropical fern craves.

Understanding Frond Types and Their Roles: Observing the plant closely, I gained a deeper appreciation for the interplay between its two frond types. The sterile basal fronds, which initially appeared to be merely structural, would periodically turn brown and dry. This browning is a normal and vital part of their lifecycle, not a sign of distress. These mature, dried shield fronds continue to play a crucial role in shielding the fern’s root system, absorbing and retaining moisture, and slowly releasing accumulated nutrients from trapped debris. Simultaneously, the fertile fronds matured, developing the distinctive spore patches on their undersides, indicating their readiness for reproduction.

Pruning Insights: A crucial lesson I learned was the hands-off approach to pruning. Unlike many houseplants, staghorn ferns generally do not require pruning. In fact, removing brown fronds, a common mistake made by new growers, can severely harm or even kill the plant. These seemingly “expired” fronds are vital to the fern’s health and longevity. I only removed sterile fronds if they had completely detached or were barely hanging on. Light pruning to remove truly dead or damaged fronds can be done in early spring to enhance the plant’s appearance.

Growth Milestones: The growth of P. elephantotis is highly seasonal, a rhythm I became attuned to. Each spring, the previous year’s shield fronds would naturally senesce and die back, making way for a flush of new shield fronds that would emerge vigorously during the summer months. Once these new shield fronds had established, the fertile fronds would then begin their impressive growth, unfurling to their full, rounded glory. Horticultural advice suggests that gently trimming back the tops of the shield fronds can encourage them to grow more erectly. Within these first few years, my fern grew considerably, reaching a height and width of 2-3 feet , a significant step towards its mature, majestic form.

Chapter 4: A Mature Masterpiece (Year 3 and Beyond)

Years have passed, and my Elephant Ear Fern is now a true spectacle, a testament to patience, consistent care, and a deep appreciation for its unique biology. Its massive fronds drape gracefully, a living sculpture that commands attention. It continues to produce pups, offering opportunities to share its beauty with others, and I marvel at its enduring resilience.

Long-Term Maintenance: Maintaining this mature masterpiece involves a continuation of the established care routines. The consistent moisture regimen, high humidity, and bright, indirect light remain paramount. As the plant matures, the frequency of fertilization might be slightly reduced, but regular feeding during the active growing season is still beneficial.

Lifespan Expectations: One of the most rewarding aspects of cultivating Platycerium elephantotis is its incredible longevity. These ferns are truly long-lived, capable of thriving for many decades, often exceeding 50 years. There are even documented cases of specimens flourishing for an astonishing 80 to 90 years. This makes the initial investment in understanding its specific needs a truly long-term commitment to a living legacy.

Managing Mature Plants: Given their potential to reach an overall height of six feet, with shield leaves over 2.5 feet across, and even individual leaves extending 8-10 feet in ideal conditions , ensuring adequate space and a robust, sturdy mounting structure becomes increasingly important. As the plant grows heavier, its support system must be capable of bearing the considerable weight.

Pup Production: A sign of a thriving, mature P. elephantotis is its tendency to produce pups freely, especially in warm, bright environments. These offshoots provide a natural means of propagation and also offer an opportunity to manage the overall size and weight of the parent plant. Division of these pups, best performed in the spring, is an excellent way to create new plants or to maintain the vigor of the original specimen. While some

Platycerium species can take 10-20 years to completely encircle a tree trunk with their pups, forming a stunning ring-shaped cluster ,

P. elephantotis offers a more manageable growth habit for home cultivation.

The journey with Platycerium elephantotis is a continuous learning experience, a partnership with nature. The success in cultivating this plant stems from recognizing and actively mimicking its natural environment. The “time-lapse” perspective of its growth reveals that consistent, adaptive care, such as adjusting watering for seasonal changes or understanding the purpose of browning fronds, aligns perfectly with the plant’s inherent biological rhythms. This approach transforms plant care from a rigid set of rules into an intuitive, responsive dialogue, fostering a deeper connection and appreciation for this magnificent botanical marvel.

IV. Cultivation Mastery: Advanced Care and Troubleshooting

Water Quality: Understanding Sensitivity to Chlorine, Fluoride, and Hard Water

The quality of water used for Platycerium elephantotis cultivation is a critical, though often overlooked, factor. While the general sensitivity of Platycerium species to tap water components can vary (for instance, P. ridleyi is noted as more sensitive than P. bifurcatum or P. superbum) , epiphytes, by their very nature, are inherently susceptible to water-deficit stress due to their lack of direct contact with soil. They also absorb water directly through their fronds , meaning any dissolved chemicals can have a more direct impact.

Chlorine: Many municipal water supplies contain chlorine for disinfection. While low concentrations are generally tolerated by most plants, sensitive species may develop brown leaf tips over extended periods of exposure. To mitigate this, letting tap water sit in an open container for 24 hours allows chlorine to dissipate through evaporation.

Fluoride: Unlike chlorine, fluoride cannot be removed by simply letting water sit. It can cause brown spots or leaf tip burn in sensitive plants, such as spider plants and dracaenas.

Hard Water: Water with high levels of dissolved minerals, like calcium and magnesium, is termed “hard water.” Over time, these minerals can accumulate in the growing medium, leading to issues such as yellowing leaves, stunted growth, and overall poor plant health, particularly for plants that prefer acidic conditions. While bottom-watering is a common and effective method for staghorn ferns, it can contribute to the buildup of these salts; occasional top-watering can help flush them out. Furthermore, water softened by salt pellets, though beneficial for household use, is detrimental to plants and should be avoided.

Considering the epiphytic nature of Platycerium elephantotis and the general vulnerability of ferns to water impurities, a proactive approach to water quality is prudent. Even without explicit data confirming P. elephantotis‘s high sensitivity to these specific chemicals, the plant’s unique physiology, which involves absorbing water directly through its fronds, suggests that dissolved chemicals could have a more direct and immediate impact compared to soil-grown plants. Therefore, as a best practice, using distilled water, collected rainwater, or reverse osmosis (RO) water is highly recommended. If tap water must be used, allowing it to sit for 24 hours to off-gas chlorine is a beneficial preventative measure. This attention to water quality helps minimize potential long-term stress and supports the plant’s optimal health.

Nutrient Deficiencies: Identification and Remediation

Like all living organisms, Platycerium elephantotis requires a balanced array of nutrients for robust growth. Deficiencies can manifest in various symptoms, often impacting leaf appearance and overall vigor.

- Nitrogen (N) Deficiency: This is commonly seen as a general yellowing, or chlorosis, that begins on older leaves, progressing from the tips inward. The entire plant may appear pale and yellowish-green with spindly stalks. Severe nitrogen deficiency can also lead to premature flowering.

- Phosphorus (P) Deficiency: Symptoms typically appear on young plants, with older leaves turning dark green, sometimes with reddish-purplish tips and margins. Growth may be slowed, and bronzing or necrotic (dead) patches can develop on heavily affected leaves.

- Potassium (K) Deficiency: This often presents as yellowing and necrosis along the margins of lower leaves. Young leaves may show rusty-brown, dehydrated, and upward-curled margins and tips. Weak stems are another indicator.

- Magnesium (Mg) Deficiency: Characterized by yellow to white interveinal striping on lower leaves. Older leaves may take on a reddish-purple hue, sometimes accompanied by small, dead, round spots.

- Iron (Fe) Deficiency: This causes interveinal chlorosis (yellowing between veins) that typically begins on the youngest, newest growth.

To address nutrient deficiencies, the primary remediation involves applying a balanced, diluted liquid fertilizer during the active growing season. Ensuring the growing medium’s pH is appropriate for the plant (neutral to acidic) also facilitates nutrient uptake.

Common Pests and Diseases: Symptoms, Identification, and Organic/Chemical Treatments

Staghorn ferns are generally considered relatively resilient and not prone to a wide array of diseases. However, like any cultivated plant, they can occasionally encounter specific pests and fungal issues. The most commonly reported pests include scale insects and mealybugs.

Diseases:

- Root Rot: This is a prevalent issue, primarily caused by overwatering or inadequate air circulation around the root system. Symptoms include abnormal frond coloring, decay at the plant’s base, wilting, and can ultimately lead to plant death. Prevention is key, focusing on proper watering techniques and ensuring good air circulation.

- Leaf Blotch / Dark Spots: These are fungal diseases, often caused by genera like Alternaria or Phyllosticta, resulting in irregular browning, tissue death, and dark patches on fronds. High humidity, poor air circulation, and consistently damp conditions favor their development.

- Whole Leaf Withering / Leaf Wilting / Leaf Tip Withering: These conditions manifest as fronds drying out, drooping, losing vigor, and potentially dying prematurely. Causes can range from underwatering and dry air to various pathogens or adverse environmental conditions.

- Black Mold / Soil Fungus / Mushrooms: These fungal problems are typically linked to excessive humidity, poor ventilation, and persistently damp conditions. Symptoms include the appearance of fungal bodies, discolored fronds, and decay.

- Yellow Edges / Leaf Yellowing: Often indicative of improper watering or light conditions, or underlying nutrient deficiencies.

Pests:

- Scale Insects: These small, sap-sucking insects attach themselves to the leaves and stems. Infestation symptoms include sticky honeydew on leaves, the formation of sooty mold, yellowing foliage, stunted growth, and in severe cases, leaf drop.

- Mealybugs: Another type of sap-sucking insect, mealybugs are identified by sticky residue and white, cotton-like masses on the fronds, leading to weakened growth.

- Thrips: These are small, winged insects that feed by sucking sap from the fronds. Their presence results in streaks, silvery speckling, frond deformation and curling, leaf drop, and stunted growth. Thrips are most active during warm, dry conditions.

- Spider Mites: These tiny arachnids cause discoloration and damage to fronds.

- Snails and Slugs: These gastropods can cause physical damage by eating away at the fronds.

Treatments (General):

- Non-Pesticide Approaches: The first line of defense often involves cultural and manual methods. This includes promptly removing any visibly infected or heavily infested fronds , improving air circulation around the plant , and watering from below to prevent wetting the fronds, which can foster fungal growth. Isolating affected plants can prevent the spread to healthy specimens. For pests like scale or thrips, strong water jets can physically dislodge them , and scale insects can also be manually scraped or wiped off. Maintaining higher humidity can deter thrips , and keeping the growing area clean of plant debris reduces breeding sites for pests.

- Pesticide Approaches (as a last resort): If non-pesticide methods prove insufficient, chemical treatments may be considered. Fungicides containing copper or mancozeb can be applied for fungal diseases, following label instructions. For insect pests, insecticidal soaps are effective against thrips , while systemic insecticides (such as imidacloprid for scale and mealybugs) or horticultural oils can be used to suffocate scale insects. Regular inspection of the plant, at least bi-weekly during warmer months, is advised to catch issues early.

Environmental Challenges and Adaptations

Epiphytes like Platycerium elephantotis face unique environmental challenges in their natural arboreal habitats, particularly regular water and nutrient stress due to their lack of direct soil contact. Over evolutionary time, they have developed remarkable adaptations to cope with these conditions. For instance,

Platycerium bifurcatum, a close relative, exhibits specialized anatomical features like thick cuticles and trichomes (hairs) on its fronds, which help protect against excessive water loss. These ferns also possess the ability to tolerate low relative water content and can function with closed stomata during dry periods, conserving precious moisture.

A truly fascinating adaptation observed in some Platycerium species, notably P. bifurcatum, is the formation of cooperative groups or “colonies”. These colonies function in a manner akin to eusocial animal societies, where individual plants work together to build a communal “nest” that serves as a collective store for water and nutrients. Within these colonies, a division of labor occurs: “nest” fronds (sterile, disk-shaped) are primarily responsible for soaking up water and trapping detritus, while “strap” fronds (thinner, green, and reproductive) deflect water towards the center of the aggregation and bear the primary reproductive load. This collective strategy, supported by interconnected root networks, significantly enhances the colony’s ability to combat water and nutrient stress in harsh epiphytic environments. While this eusocial-like behavior is extensively studied in

P. bifurcatum, the underlying principles of communal adaptation to resource scarcity are likely shared across the genus, including P. elephantotis. Furthermore, sudden draughts can cause the fronds to turn brown , underscoring the need to place these plants in sheltered locations where environmental conditions are stable.

The apparent contradiction between some descriptions of staghorn ferns as “low maintenance” and others as requiring a “high care level” or being “hard” to care for can be reconciled by understanding the nuances of their cultivation. The “low maintenance” aspect typically refers to the fact that once a

Platycerium is established and its specific environmental needs are consistently met, it does not demand constant intervention like frequent pruning. However, achieving these precise conditions, particularly the delicate balance of high humidity and consistent moisture without leading to root rot, requires a significant degree of attention, knowledge, and responsiveness from the gardener. This initial setup and the ongoing precision required to mimic its natural rainforest habitat are what contribute to the perception of a “high care level” or “hard” difficulty, especially for those unfamiliar with epiphytic plants. Therefore, while the plant is not inherently difficult in its long-term needs, the expertise required to establish and maintain its ideal environment makes it a plant that rewards dedicated and informed care.

Table 1: Common Pests & Diseases of Platycerium elephantotis

| Pest/Disease | Symptoms | Causes | Treatment (Non-Pesticide) | Treatment (Pesticide) |

| Diseases | ||||

| Root Rot | Abnormal frond coloring, decay at plant base, wilting, potential death | Overwatering, poor air circulation, damp conditions | Improve air circulation, adjust watering frequency | N/A (focus on prevention) |

| Leaf Blotch / Dark Spots | Irregular browning, tissue death, dark patches on fronds | Fungal species (Alternaria, Phyllosticta), high humidity, poor air circulation | Remove infected fronds, improve air circulation, water from below | Fungicides (copper, mancozeb) |

| Whole Leaf Withering / Leaf Wilting / Leaf Tip Withering | Fronds dry out, droop, lose vigor, die prematurely | Underwatering, dry air, various pathogens/conditions | Adjust watering, increase humidity, remove affected fronds | N/A (depends on underlying cause) |

| Black Mold / Soil Fungus / Mushrooms | Fungal bodies on surfaces, discolored fronds, decay at plant base | High humidity, poor ventilation, damp conditions | Improve air circulation, adjust watering, remove fungal bodies | N/A (focus on environmental control) |

| Yellow Edges / Leaf Yellowing | Yellowing along frond edges, discoloration, wilting | Nutrient deficiencies, improper watering/light conditions | Adjust watering/light, provide balanced fertilizer | N/A (address underlying cause) |

| Pests | ||||

| Scale Insects | Sticky honeydew, sooty mold, yellowing foliage, stunted growth, leaf drop | Small, sap-sucking insects | Manual removal (scrape/wipe), strong water jets, isolate plant | Systemic insecticides, horticultural oil |

| Mealybugs | Sticky residue, white cotton-like masses on fronds, weak growth | Sap-sucking insects | Manual removal, water sprays, isolate plant | Systemic insecticides (e.g., imidacloprid) , insecticidal soaps |

| Thrips | Streaks, silvery speckling, frond deformation/curling, leaf drop, stunted growth | Small, winged sap-sucking insects, warm/dry conditions | Isolate plant, strong water jets, prune infested fronds, maintain humidity | Insecticidal soaps, systemic insecticides |

| Spider Mites | Discoloration and damaged fronds | Mite infestation | Increase humidity, water sprays | Miticides (if severe) |

| Snails and Slugs | Chewed fronds, physical damage | Gastropod predation | Manual removal, barriers | Baits (if severe) |

V. Elephant Ear Fern in Context: Comparisons and Unique Symbioses

Platycerium elephantotis vs. Platycerium wandae: A Morphological Showdown

Comparing Platycerium elephantotis with other species within the genus highlights its unique morphological characteristics. P. elephantotis is readily identified by its large, unforked, and distinctly rounded fertile fronds, which are the source of its common name, “Elephant Ear Staghorn Fern”. The spores on this species are found at the bottom of these characteristic rounded fronds , and its sterile fronds are tall and arched.

In contrast, Platycerium wandae is often cited as the largest Platycerium species, capable of growing approximately 33% larger than P. superbum. A key distinguishing feature of

P. wandae is the presence of dense, unique frills that grow around its growth bud, a characteristic not observed in other Platycerium species. Its fertile fronds are bifurcated (forked) and possess distinct lower and upper divisions of spore patches that originate relatively close to the bud. The upper spore patch is broad and wide, bearing a resemblance to a ginkgo leaf, while the lower patch also features broad, lobular, trailing leafy portions. It is worth noting that very young

P. wandae specimens can be morphologically indistinguishable from other solitary Platycerium species. While both

P. elephantotis and P. wandae are impressive in size, the unforked, rounded fertile fronds of P. elephantotis clearly set it apart from the bifurcated, frilled fertile fronds of P. wandae.

Platycerium elephantotis vs. Platycerium ridleyi: Distinguishing Features

Another interesting comparison can be drawn between Platycerium elephantotis and Platycerium ridleyi. As previously described, P. elephantotis is characterized by its large, broad, and unforked fertile fronds that resemble elephant ears.

P. ridleyi, conversely, is a rare and notably smaller species within the Platycerium genus, recognized for its unique leaf pattern. Its sterile fronds possess a distinctive “waffled” or “brain matter”-like texture and are designed to completely enclose around a branch. Unlike the single, broad spore patch of

P. elephantotis, P. ridleyi bears its spores on a specialized stalked lobe. While there are suggestions that

P. elephantotis may have important ant relationships similar to those observed in P. ridleyi , their frond morphology presents a stark contrast, with

P. elephantotis displaying its broad, unforked fertile fronds against P. ridleyi‘s unique waffled sterile fronds and specialized spore-bearing structures.

The Fascinating Ant-Plant Mutualism: Scientific Insights and Observations

The natural world is full of intricate partnerships, and among the most compelling are the mutualistic symbiotic relationships between plants and ants. In these associations, both parties benefit: plants often provide shelter (domatia) or food (nectar, food bodies), and in return, ants offer protection against herbivores, competing vegetation, or pathogens. These relationships can range from obligate, where neither species can survive without the other, to facultative, where the association is beneficial but not strictly necessary for survival.

A truly groundbreaking area of research has revealed a profound level of social organization within certain Platycerium species. Studies, particularly on Platycerium bifurcatum, suggest that these ferns may exhibit a complex, interdependent society, a characteristic previously thought to be limited to animals like ants and termites. This phenomenon, termed eusociality, involves overlapping generations living together and forming castes with a division of labor. In

P. bifurcatum colonies, the “nest” fronds, which are sterile, disk-shaped, and brown, primarily function to soak up water and trap detritus, forming a communal resource store. Conversely, the thinner, green “strap” fronds are more involved in reproduction and direct water towards the center of the aggregation. This remarkable division of labor, supported by interconnected root networks that allow nest fronds to supply water to strap fronds, is a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that helps the entire colony combat the water and nutrient stress inherent in harsh epiphytic environments. The observation of high genetic relatedness among individuals within these colonies further reinforces the comparison to eusocial insect societies. This discovery represents a significant shift in our understanding of plant biology, demonstrating a level of cooperative organization that challenges traditional scientific paradigms and highlights the profound ways in which life forms adapt and interact to ensure survival. While the detailed research on this eusocial-like behavior is primarily focused on

P. bifurcatum, the implications are far-reaching for the entire Platycerium genus, suggesting that other species, potentially including P. elephantotis, may also employ similar communal strategies, even if less extensively studied.

Regarding specific ant associations with Platycerium elephantotis, while some sources suggest that P. elephantotis may have important ant relationships, similar to P. madagascariense and P. ridleyi (which are known to be consistently colonized by ants, even indoors) , the provided research does not offer extensive, in-depth scientific studies detailing the precise nature of the ant-plant mutualism specifically for

P. elephantotis. The broader scientific literature on ant-plant mutualism, as seen in examples like Acacia trees and Macaranga plants, provides a framework for understanding these interactions. In these systems, ants can contribute to the stability of plant structures through fungal networks and can even absorb water, protecting nests from flooding while tolerating drought. However, without specific research, it is important to acknowledge that while

P. elephantotis is mentioned in the context of ant relationships, the detailed scientific evidence for its particular symbiotic interactions with ants is not as thoroughly documented as for some other Platycerium species or general ant-plant systems. This indicates an area ripe for further botanical and ecological investigation.

VI. Conclusion: A Living Legacy

The Platycerium elephantotis, with its distinctive, unforked, and broad fronds resembling majestic elephant ears, stands as a unique and captivating specimen within the diverse Platycerium genus. Its aesthetic appeal is matched by its remarkable resilience and adaptability as an epiphyte, capable of thriving for many decades, potentially living for 50 years or more, and even reaching impressive ages of 80 to 90 years under optimal conditions. This fern’s fascinating biological adaptations, including its specialized sterile and fertile fronds that create a self-sustaining nutrient system, underscore its evolutionary success in challenging arboreal environments. The potential for eusocial-like communal growth observed in related

Platycerium species further highlights the genus’s sophisticated strategies for survival and resource management.

Cultivating Platycerium elephantotis is a deeply rewarding endeavor that encourages a nuanced approach to plant care. While it may carry a reputation for difficulty, this is often a misunderstanding of its specific needs rather than an inherent challenge. The key to its success lies in understanding and consistently providing its unique requirement for even moisture, ensuring it never fully dries out, a critical distinction from many other staghorn ferns. Embracing the specific environmental conditions—bright, indirect light, high humidity, and appropriate mounting—transforms its cultivation into a harmonious partnership with nature. Viewing the plant’s development as a “time-lapse” journey allows for a deeper appreciation of each growth milestone and adaptation, from the emergence of new fronds to the vital role of the browning shield fronds. This detailed understanding of its biology, coupled with responsive care, allows the gardener to cultivate not just a plant, but a living legacy, a truly unique and long-lived botanical marvel that enriches any space it inhabits.

If i die, water my plants!