I. Introduction: Unveiling the Elusive Four-Forked Staghorn Fern

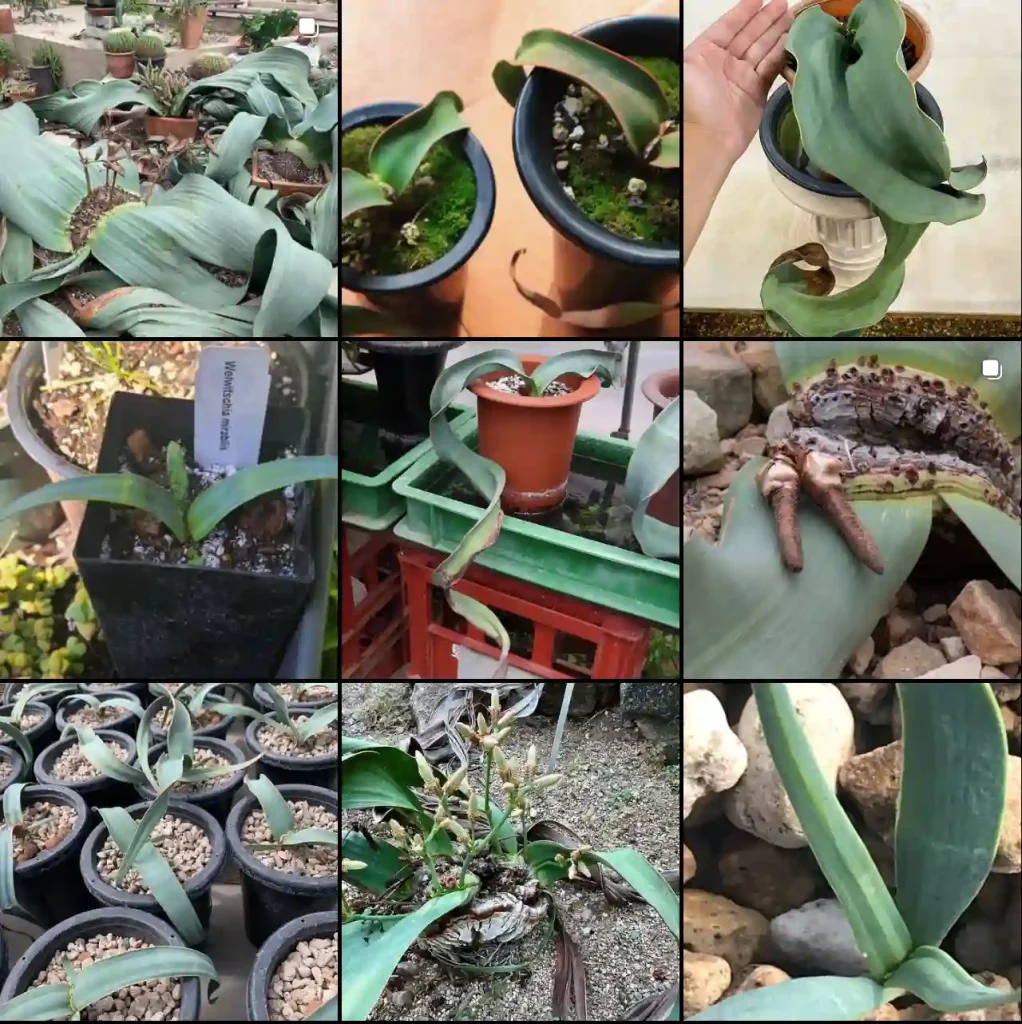

Staghorn ferns, with their striking, almost sculptural beauty, have long captivated plant enthusiasts. These unique botanical specimens, known for their distinctive antler-like fronds, transform any space they inhabit into a living art installation. Among the diverse members of this fascinating genus, Platycerium quadridichotomum stands out as a particularly rare and captivating species, presenting a rewarding challenge for dedicated growers. Its elusive nature and specific requirements make its successful cultivation a testament to horticultural expertise.

The genus Platycerium encompasses approximately 17 to 18 accepted species of epiphytic ferns. As epiphytes, these ferns do not typically grow in soil in their natural habitats. Instead, they are found clinging to the branches of trees or on rocks in the tropical and subtropical rainforests of Africa, Australia, South America, and Southeast Asia. In these environments, they absorb essential nutrients from organic matter that becomes trapped within their root structures or in the crevices of their host surfaces. Their common names, “Staghorn Fern” or “Elkhorn Fern,” are derived from the remarkable resemblance of their fertile fronds to the impressive antlers of male deer or elk.

What truly sets Platycerium quadridichotomum apart within this intriguing genus is its specific origin and unique adaptations. Unlike most Platycerium species that thrive in consistently humid rainforests, P. quadridichotomum hails from the semi-arid western side of Madagascar. This unusual habitat dictates a fascinating and challenging dormancy cycle, during which the plant appears to “die back” significantly during Madagascar’s lengthy dry season, only to reawaken with renewed vigor when the rains return. Its name,

quadridichotomum, literally translates to “four-forked,” a direct descriptor of its defining fertile fronds, which often branch multiple times to form four distinct tips. This combination of a unique Madagascan origin, distinctive morphology, and an unusual dormancy period positions

P. quadridichotomum as a truly singular and demanding species within the Platycerium genus. The limited detailed information available on this particular species underscores its rarity and the specialized knowledge required for its successful cultivation, making it a prized specimen for advanced enthusiasts.

II. Botanical Deep Dive: The Anatomy and Habitat of Platycerium quadridichotomum

Botanical Classification and General Characteristics

Platycerium quadridichotomum belongs to a specific botanical lineage, placing it firmly within the plant kingdom. Its full scientific classification is as follows: Kingdom Plantae, Clade Tracheophytes, Division Polypodiophyta, Class Polypodiopsida, Order Polypodiales, Suborder Polypodiineae, Family Polypodiaceae, Subfamily Platycerioideae, and Genus Platycerium Desv.. This classification establishes its identity as a true fern, specifically a member of the polypody family, which is characterized by its unique reproductive structures and growth habits.

Adult Platycerium plants, known as sporophytes, develop tufted root systems that emerge from a short rhizome. A defining characteristic of the genus is the production of two distinct types of fronds, each serving a specialized function. These include basal fronds and fertile fronds, which contribute to the plant’s unique appearance and survival strategy.

Natural Habitat & Adaptations

The native home of Platycerium quadridichotomum is the semi-arid western region of Madagascar. This habitat presents a stark contrast to the consistently humid rainforests where most other

Platycerium species thrive, highlighting a remarkable evolutionary divergence for this particular fern. Unusually, P. quadridichotomum often grows on limestone rocks in this region, rather than exclusively on trees, further distinguishing it from its arboreal counterparts. It is, in fact, the only

Platycerium species found in this specific dry area of Madagascar.

The climate of its native habitat is characterized by an extreme dry season, which can persist for up to six months. For instance, in Mahajanga, a major city in western Madagascar where this species grows, rainfall averages less than 0.1 inches from May through October, with June often experiencing almost no rain. This severe environmental pressure has led to the development of remarkable adaptations in

P. quadridichotomum. During these lengthy dry periods, the plant enters a state of dormancy. Its shield fronds become crispy and brown, and its fertile fronds tightly roll up, giving the plant the appearance of being dead. This physiological response is a crucial survival mechanism, reducing the plant’s surface area to minimize water loss and protecting its densely hairy undersides. As soon as the rains return,

P. quadridichotomum rapidly resumes lush, emerald green growth, showcasing its incredible resilience and ability to cycle between dormancy and active growth in response to environmental cues. This unique adaptation to xeric conditions, as seen in other drought-tolerant

Platycerium species like P. veitchii, underscores the genus’s diverse survival strategies.

Frond Forms: The Dual Beauty

Platycerium quadridichotomum, like other members of its genus, exhibits dimorphic fronds, meaning it produces two distinct types of leaves, each with specialized functions.

Basal Fronds (Shields)

The basal fronds are sterile, meaning they do not produce spores. These fronds are typically small, flat, and shield- or kidney-shaped, growing tightly against the surface the fern is attached to. Their primary role is to cover and protect the plant’s root structure from damage and desiccation. Over time, these fronds mature, often turning brown and forming a nest-like structure that effectively collects water and fallen organic debris, such as leaves, forest litter, and even animal droppings. This accumulated material decomposes, creating a natural “compost” system that provides a continuous supply of nutrients to the fern’s roots over many years.

For P. quadridichotomum specifically, its shield fronds are described as tall for a relatively small plant, spreading outward at the tip without distinct lobes. They are not thick, corky shields designed to store water, but rather resemble those of

P. stemaria. During the wet season, these fronds are emerald green. However, their most notable characteristic is their response to the dry season: they turn crispy brown and can roll up lengthwise like tubes, exposing their protected, hairy undersides to the outside and significantly decreasing their surface area to conserve moisture. The number of shield fronds produced can vary greatly from year to year, reflecting the plant’s adaptive response to its environment.

Foliar Fronds (Antler-like)

The foliar fronds are the fertile fronds, responsible for reproduction. These are the dramatic, distinctive fronds that give the genus its common “staghorn” or “elkhorn” moniker. They are typically long, branching, and can grow significantly, sometimes up to 4 feet in length and 1 foot in width. Their appearance can vary, ranging from antler-shaped to fan-shaped or even elephant ear-shaped, and they are generally green, bluish-green, or gray-green. Spore cases, known as sori, are borne on the underside of these fronds, often in large clusters.

For P. quadridichotomum, the name itself describes these fronds: they often branch multiple times to form four distinct tips, giving them a “four-forked” appearance. These fertile fronds typically hang downwards and often have wavy edges. The upper surface may appear hairy in bright light, while the lower surface is densely covered with tan hairs. The spore patch, which is dark brown, is usually located in the area of the second frond division, similar to

P. andinum. During dry periods, these fronds also roll tightly, appearing dead, before unfurling into lush green with the return of moisture. This dual frond system, with its specialized adaptations, is central to the survival and unique aesthetic of

P. quadridichotomum.

Size and Appearance

The overall size of Platycerium plants, including P. quadridichotomum, can vary, but generally, they range from 2 to 3 feet in both height and width. Individual foliar fronds, however, can extend up to 4 feet in length and 1 foot in width. The specific size, shape, and color of the fronds are influenced not only by the species but also by the growing conditions provided. Fronds can exhibit various forms, including deeply divided, forked, strap-like, heart-shaped, or lobed patterns. Some fronds arch elegantly upwards, while others cascade downwards in a pendulous fashion. Many species, including

P. quadridichotomum, also possess a fuzzy texture on their fronds, which is due to a coating of fine white hairs or trichomes. These trichomes serve a protective function, shielding the plant from sun damage and desiccation, particularly in species adapted to drier conditions.

III. Cultivation: A Time-Lapse Guide to Nurturing Platycerium quadridichotomum

Cultivating Platycerium quadridichotomum is a journey that requires understanding its unique adaptations and providing conditions that mimic its challenging natural environment. While general Platycerium care guidelines apply, the specific needs of this Madagascan native necessitate careful attention to detail.

Light and Temperature Requirements

Platycerium quadridichotomum, like most staghorn ferns, thrives in bright, indirect light. Direct, harsh sunlight should be avoided, as it can easily scorch or bleach the delicate fronds, leading to brown spots or blotching. In their natural habitat, these ferns often grow under the tree canopy, receiving dappled sunlight. When grown indoors, an east-facing window or a location with filtered light is often ideal. While they can tolerate more sunlight if provided with ample water, warmth, and humidity, caution is always advised to prevent frond burn.

The ideal temperature range for Platycerium quadridichotomum is between 40°F and 100°F (4°C and 38°C). However, they generally prefer warmer conditions, ideally between 50°F and 100°F , or more specifically, 55°F to 75°F. It is crucial to protect these ferns from frost; if temperatures are expected to drop below 40°F (or 50°F for general staghorn ferns), they should be brought indoors. While mature staghorn ferns can briefly survive freezing temperatures, consistent warm, humid conditions are essential for their thriving, especially when young. Temperature fluctuations should be gradual, as sudden changes can stress the plant, potentially leading to brown shield fronds or stunted new growth.

Water and Humidity Management

Proper watering is a critical component of successful Platycerium cultivation. These ferns require frequent and consistent watering, but the base or growing medium should be allowed to dry out somewhat between waterings to prevent root rot, a common issue caused by overwatering. A good rule of thumb is to water about once a week during warmer months or active growing seasons (spring and summer), and once every two to three weeks during cooler, dormant periods (fall and winter). It is important to adjust this frequency based on the specific climate and environmental conditions.

For mounted ferns, an effective watering method involves removing the fern and its mount from the wall and soaking it in a sink or large container filled with water for 10 to 20 minutes, or until the roots are fully saturated. After soaking, allow the plant to drip dry completely before re-hanging it. For potted ferns, water until it drains from the bottom, then ensure the saucer is emptied to prevent waterlogging. Filtered water or rainwater is generally preferred, and if using tap water, it is advisable to let it sit overnight to allow chlorine to dissipate. Softened water should be avoided due to its high sodium content. Signs of underwatering include crispy, browning fronds, slow growth, or curling frond tips. Conversely, overwatering can lead to soggy fronds, wilting, or mold growth.

Staghorn ferns, originating from rainforest environments, have a high humidity requirement, ideally around 60-75%. They absorb moisture from both the air and their growing medium. To increase humidity, especially in dry environments, regular misting of the fronds is recommended. Placing the fern in naturally humid areas of the home, such as a bathroom or kitchen, can also be beneficial. Grouping plants together or using a pebble tray filled with water beneath the plant can create a localized microclimate with higher humidity.

Fertilization Practices

To promote healthy and vigorous growth, Platycerium quadridichotomum benefits from regular fertilization, particularly during its active growing season in spring and summer. A diluted, balanced liquid fertilizer, such as a 10-10-10 or 20-20-20 formula, is recommended. This should be applied monthly, or twice monthly during peak growth, diluted to 1/4 to 1/2 strength of the recommended dosage. For mounted ferns, fertilization can be achieved by immersing the entire mount into a solution of water and dilute fertilizer. Alternatively, slow-release granular fertilizers formulated for epiphytes or orchids can be tucked around the basal fronds, applied 2-3 times per year according to product instructions.

During the fall and winter months, when growth naturally slows, fertilization frequency should be reduced to every other month or stopped entirely. Over-fertilization can lead to issues such as brown or burned frond tips, excessive salt buildup in the growing medium, or stunted growth. Signs of under-fertilization include slow growth, pale or yellowing fronds, or smaller than normal new growth. Natural alternatives like diluted fish emulsion or seaweed extract can also provide a balanced nutrient profile.

Mounting and Substrate

Staghorn ferns are epiphytes, meaning they naturally grow on other plants or surfaces rather than in soil. Therefore, for successful cultivation, especially as they mature, mounting them on a suitable medium is the preferred method, mimicking their natural growth habit. Small, young plants can be started in containers with a rich, well-drained potting medium like sphagnum or peat moss, but mounting becomes more logical as they grow.

Mounting is typically done by securing the fern to a wooden board, bark slab, or wired basket. The fern’s base should be embedded in a lump of moisture-retentive, well-draining organic material such as sphagnum moss, peat, or compost. Fishing line or wire can be used to keep the fern in place until it becomes established and its new fronds grow to cover the fastening material. As the fern matures, it can become quite large and heavy, potentially requiring remounting on a larger slab. For hanging baskets, lining the basket with sphagnum moss and planting the fern inside provides the necessary air circulation that mimics its natural situation. Proper mounting vastly improves the fern’s growth and stability.

Pruning and Maintenance

Staghorn ferns are low-maintenance plants. Basal fronds, or shield fronds, should generally not be removed, even when they turn brown, as this is a normal part of their lifecycle and they continue to protect the root structure and collect nutrients. These brown shield fronds eventually form a nest-like structure around the base of the plant. Foliar fronds, however, can be pruned if they are damaged, withered, or diseased. It is important to avoid pruning during dormant periods, typically winter, unless absolutely necessary. When pruning, sterilized tools should be used to prevent the spread of diseases. Care must be taken not to damage the central growing point of the fern. The white, dust-like material (trichomes) on the fronds should never be wiped away, as it serves to protect the plant from sun damage and desiccation.

IV. Propagation: Expanding Your Platycerium quadridichotomum Collection

Propagating Platycerium quadridichotomum can be a rewarding endeavor, allowing enthusiasts to expand their collection. Two primary methods are employed: division and spore propagation. While division is generally considered easier for home growers, spore propagation offers a fascinating glimpse into the fern’s life cycle.

Propagation by Division (Pups)

Most Platycerium species, including P. quadridichotomum, can be propagated by division, particularly from the small offsets or “pups” that mature plants produce under favorable conditions. This method is generally simpler and yields faster results than spore propagation.

To divide a staghorn fern:

- Select a Healthy Plant: Choose a healthy, mature plant that has produced multiple growth points or pups.

- Prepare the Plant: Water the plant thoroughly a day before division to minimize stress.

- Careful Removal: Gently remove the fern from its mounting or pot.

- Identify Divisions: Carefully identify natural separation points, ensuring each “chunk” or pup includes a leaf and a portion of the root ball.

- Cut with Sterilized Tool: Use a sharp, sterilized knife to cut the baby plants away from the parent.

- Planting New Divisions: Plant these sections individually in small pots filled with a well-draining potting mix, such as peat and compost, or a mix with coco coir.

- Post-Division Care: Keep the new divisions warm and moist in indirect sunlight until they establish roots and begin growing independently. This rooting process can take some time, requiring patience. Once rooted, the pups can be mounted like the parent plant. It is common for newly-cut divisions to take a while to root, and propagating ferns can require practice.

Propagation by Spores: A Time-Lapse Journey

Growing Platycerium from spores is a lengthier and more intricate process, revealing the fern’s two-phase life cycle, known as the alternation of generations. While challenging, it is a fascinating and rewarding experience for the patient gardener.

1. Collecting Spores: The Beginning of a New Life

Spores are produced on the underside of the fertile fronds, typically in clusters called sori. These sori usually appear as small bumps or lines, often in a symmetrical pattern, initially green and turning brown or golden as they mature. Inside the sori are sporangia, which contain the tiny, virtually invisible spores. For

P. quadridichotomum, the spore patch is dark brown and located near the second frond division.

To collect spores, a mature frond bearing sori that have turned brown should be cut and placed inside a white envelope. Within a few days, the sporangia will release the spores, appearing as fine brown dust contrasting against the white paper. Spores can be sown immediately, especially green spores which have a shorter shelf life, or stored for later use.

2. Preparing the Media and Sowing

A sterile growing medium is crucial for spore germination. A common mixture consists of peat moss and perlite. Some methods suggest layering, for example, perlite as the first layer, followed by Osmocote, and then peat moss as the top layer. The medium should be moistened but well-drained.

Spores should be sprinkled thinly and evenly over the surface of the moist, sterile medium. The container should then be covered with clear plastic or a lid to maintain high humidity and a sterile environment.

3. Germination and Gametophyte Stage: Weeks to Months

This is the initial waiting period. Spores typically germinate between 7 to 14 days after sowing (DAS). However, the appearance of visible growth can take a few weeks to several months.

The spores do not directly grow into a fern. Instead, they develop into a preliminary life stage called the prothallus (or gametophyte). These appear as small, green, generally translucent, heart-shaped growths on the surface of the potting mix, resembling liverworts or mosses. This prothallial development is characterized by the early formation of unicellular trichomes, typically observed around 30-40 DAS. Each prothallus is the sexual phase of the fern’s life cycle, producing both haploid male gametes (sperm) and one haploid female gamete (egg). In cultivation, a high concentration of gametophytes can look like a green mat on the growing medium.

4. Fecundation and Sporophyte Formation: Months to a Year+

When conditions are right, particularly with sufficient moisture, the male gametes swim to and fertilize the female gametes. This fusion creates a diploid cell, completing the alternation of generations.

After another few weeks to months, a small diploid sporeling (baby fern) will become visible. Initially, it will have just one small frond, followed by larger ones. The prothallus will eventually fade away, leaving an independent, small fern. The first growth of a new staghorn fern may not immediately resemble the mature plant, with the traditional shape typically appearing in the second generation of growth.

Waiting for the sporophyte to fully form can be a lengthy step, often taking a year or longer. For example, a sowing in October 2018 showed good gametophyte growth by April 2019. Once the young ferns are at this stage, they can be acclimated to lower humidity by gradually opening the plastic cover over a period of about a week.

5. From Baby to Mature Fern: Years of Growth

The growth of the young sporophytes accelerates considerably once they are established. While in the wild it can take 4 to 5 years for a fern to reach its full size, patient indoor gardeners can often grow most ferns to a usable size within a year or two, as they benefit from year-round growth and optimized conditions. For

Platycerium, reaching a sizable, mature fern that produces its own spores can take anywhere from 5 to 10 years.

Platycerium species grow relatively slowly in cooler climates but can grow aggressively in warm areas. With proper care, staghorn ferns can live for 50 years or more. This long-term commitment and the gradual development from a microscopic spore to a magnificent, mature plant truly embody a time-lapse journey.

V. Common Issues and Solutions: Maintaining a Healthy Platycerium quadridichotomum

Despite their resilience, Platycerium quadridichotomum can encounter various issues, primarily related to environmental conditions, pests, and diseases. Understanding these common problems and their remedies is crucial for maintaining a healthy and thriving fern.

Environmental Stressors and Symptoms

Many issues in staghorn ferns stem from improper care or unsuitable environmental conditions.

- Incorrect Light: Direct sunlight is a significant stressor, causing leaf burn, bleaching, or blotchy marks on the fronds. Symptoms include brown spots on fronds, which can also be caused by fungal infections or inconsistent watering.

- Solution: Ensure bright, indirect light. Use sheer curtains to filter harsh sun, and rotate the plant for even light exposure. Supplement with artificial grow lights if natural light is insufficient.

- Improper Watering: Both overwatering and underwatering are detrimental.

- Overwatering: This is a frequent mistake, leading to root rot and fungal infections. Symptoms include soggy fronds, wilting, a soft/mushy base, or mold growth on the mounting surface. Stem rot, a destructive fungal disease, is often triggered by overwatering or poor drainage, compromising the plant’s vascular system.

- Solution: Allow the substrate to partially dry out between waterings. Ensure good air circulation around the plant. Improve drainage in the potting mix.

- Underwatering: Can cause crispy, browning fronds, slow growth, or curling frond tips due to dehydration. Whole leaf withering, where fronds dry out and die prematurely, can also result from dehydration.

- Solution: Maintain a regular watering schedule, especially in drier climates or seasons. Regularly check moisture levels of the growing medium.

- Overwatering: This is a frequent mistake, leading to root rot and fungal infections. Symptoms include soggy fronds, wilting, a soft/mushy base, or mold growth on the mounting surface. Stem rot, a destructive fungal disease, is often triggered by overwatering or poor drainage, compromising the plant’s vascular system.

- Low Humidity: A common cause of distress, leading to foliar fronds turning brown, drying out, and dropping.

- Solution: Mist regularly, use a pebble tray, group plants, or place in naturally humid rooms like bathrooms or kitchens.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Can manifest as stunted growth, pale or yellowing fronds, or smaller new growth. Yellow edges on fronds specifically signal potential issues with watering or light, but can also indicate nutrient imbalances.

- Solution: Follow recommended fertilization schedules during the growing season.

Pests and Diseases

While generally resilient, Platycerium can occasionally be affected by pests and fungal diseases.

- Pests: Pests are relatively rare but can include scale insects, mealybugs, spider mites, whiteflies, snails, and slugs.

- Scale Insects: These pests suck sap, diminishing plant vigor, leading to leaf yellowing and decline.

- Treatment: Manual removal (gently scraping with a soft brush or cloth), strong water sprays to dislodge immature insects, or isolation of infested parts. For severe infestations, systemic insecticides or horticultural oil can be applied to suffocate or kill the insects.

- Mealybugs & Spider Mites: Spider mites thrive in dry air, causing discoloration and damaged fronds. Mealybugs also suck sap.

- Treatment: For minor spider mite infestations, a good shower with a shower head can dislodge them. A solution of neem oil and castile soap can be used to wipe leaves. For widespread infestations, predatory insects (e.g., predatory mites for spider mites, lacewings/ladybugs for mealybugs) or systemic pesticides are options.

- Whitefly, Snails, Slugs, Weevils: These can cause physical damage, stunted growth, or weakened health.

- Scale Insects: These pests suck sap, diminishing plant vigor, leading to leaf yellowing and decline.

- Fungal Diseases: Fungal issues are often linked to overwatering and poor air circulation.

- Stem Rot / Root Rot: Destructive fungal diseases that compromise plant health, leading to wilting and potential death. They affect the vascular system, hindering nutrient and water transport. Most active in warm, humid conditions.

- Treatment: Improve drainage, remove infected parts, and apply suitable fungicides (e.g., copper or mancozeb). Prevention includes proper watering practices and using disinfected pruning tools.

- Black Mold, Leaf Rot, White Blotch, Soil Fungus: These fungal diseases cause discolored fronds, spots, reduced growth, and can lead to plant death if untreated.

- Treatment: Improve ventilation, manage humidity, remove affected parts, and apply fungicides as needed.

- Stem Rot / Root Rot: Destructive fungal diseases that compromise plant health, leading to wilting and potential death. They affect the vascular system, hindering nutrient and water transport. Most active in warm, humid conditions.

- Other Issues:

- Scars: Physical disfigurement and weakened health due to tissue damage.

- Leaf Wilting: General drooping of foliage, often indicating stress from watering issues or environmental factors.

- Non-base branch withering: Premature leaf loss and wilting.

Regular inspection of the plant for early signs of distress is crucial for preventing further damage and maintaining overall plant health. Quarantining new plants can also prevent the introduction of pests.

VI. Unique Comparisons and Adaptations: P. quadridichotomum vs. Other Staghorn Ferns

The Platycerium genus boasts a fascinating diversity, and comparing P. quadridichotomum to other prominent species highlights its unique evolutionary path and cultivation challenges. While all Platycerium share the defining characteristics of epiphytic growth and dimorphic fronds, their adaptations to specific native habitats result in distinct appearances and care requirements.

P. quadridichotomum vs. Rainforest Natives

Most Platycerium species, such as P. bifurcatum (Common Staghorn Fern or Elkhorn Fern) ,

P. superbum (Superb Staghorn Fern) , and

P. grande (Grand Staghorn Fern) , originate from consistently humid rainforest environments. These species thrive with high humidity, consistent moisture, and protection from direct sunlight, often growing high in the canopy where they receive dappled light. For instance,

P. bifurcatum is known for being more cold-hardy and fast-growing, making it a popular beginner choice.

P. superbum is a large species native to Australia, forming a nest of overlapping, furry, shield-like leaves and can grow to be quite substantial.

P. grande, from the Philippines, is also large, with fan-shaped fronds.

In stark contrast, Platycerium quadridichotomum is unique for its origin in the semi-arid western side of Madagascar. This region experiences a lengthy dry season, which can last up to six months. This extreme difference in habitat dictates its peculiar dormancy cycle, where its shield fronds turn crispy brown and fertile fronds roll up, appearing dead, only to resume lush green growth with the return of rains. This adaptation for drought tolerance, resembling the xeric adaptations of species like

P. veitchii (Silver Elkhorn or Desert Staghorn) from semi-arid Australia , sets

P. quadridichotomum apart from its rainforest-dwelling relatives. While P. veitchii also exhibits drought tolerance and a silvery sheen from white hairs, P. quadridichotomum‘s dramatic dormancy and preference for limestone rocks in its native habitat are particularly distinctive.

Furthermore, P. quadridichotomum‘s unique characteristic of often growing on limestone rocks rather than exclusively on trees is a notable deviation from the typical epiphytic habit of most Platycerium species. It is, in fact, the only

Platycerium species found in this specific dry region of Madagascar. This specific ecological niche and its corresponding adaptations underscore its rarity and the specialized care it requires, differing from the more broadly cultivated species that prefer consistent humidity.

Frond Morphology Comparisons

The fertile fronds of Platycerium species are their most striking feature, and their shapes vary considerably.

- P. quadridichotomum is named for its distinctive fertile fronds that often branch multiple times to form four tips, hanging downwards with wavy edges.

- P. bifurcatum (Elkhorn Fern) is known for its deeply lobed, antler-shaped fronds.

- P. grande has large, upright, fan-shaped fronds that form a nest.

- P. madagascariense (Madagascar Staghorn Fern), also from Madagascar, is a rare species with an unusual leaf shape, but it originates from cloud forests, not semi-arid regions like P. quadridichotomum.

- P. ridleyi (Ridley’s Staghorn Fern) is the smallest species with a unique leaf pattern and specialized stalked lobes for spore patches.

- P. wandae (Queen Staghorn) from New Guinea is truly enormous, reaching over two meters at maturity, with upright shield fronds forming a massive basket and two-lobed fertile fronds.

- P. andinum, the only South American species, has notably thin fronds that can grow over 5 feet long and produces pups that can circle a tree trunk over decades.

The specific appearance of P. quadridichotomum‘s shield fronds also differs. They are tall for its size, spreading outward at the tip without lobes, and are not thick or corky like water-storing shields, resembling P. stemaria instead. This morphological distinction, combined with its unique dormancy, makes

P. quadridichotomum a highly specialized and intriguing member of the Platycerium family, appealing to collectors seeking truly distinctive and challenging specimens.

VII. Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Platycerium quadridichotomum

The journey of cultivating Platycerium quadridichotomum is one that deeply connects the grower to the plant’s remarkable evolutionary history and its enduring resilience. This elusive four-forked staghorn fern, originating from the semi-arid western regions of Madagascar, stands as a testament to nature’s adaptability. Its unique ability to enter a profound dormancy during prolonged dry seasons, only to burst forth with lush, emerald green growth upon the return of rains, is a captivating survival strategy that distinguishes it from its more common rainforest relatives. The literal “four-forked” nature of its fertile fronds and its unusual preference for growing on limestone rocks further underscore its distinctiveness within the Platycerium genus.

Successful cultivation of P. quadridichotomum hinges on understanding and replicating, as closely as possible, the challenging conditions of its native habitat. This involves providing bright, indirect light, maintaining warm temperatures while protecting from frost, and carefully managing watering to allow for brief dry periods between saturations. Humidity, though crucial, must be balanced with adequate air circulation to prevent fungal issues. Furthermore, the practice of mounting these epiphytic ferns on suitable substrates mimics their natural growth habit and is essential for their long-term health and stability.

The propagation of P. quadridichotomum, whether through the relatively simpler division of pups or the intricate, time-lapsed process of spore cultivation, offers a profound engagement with the fern’s life cycle. From a microscopic spore to a heart-shaped gametophyte, and finally to a mature, antler-fronded sporophyte, the journey can span years, demanding patience and dedication. However, the reward is a magnificent, sculptural plant that can live for decades, becoming a living legacy.

The challenges associated with P. quadridichotomum cultivation, from specific environmental needs to potential pest and disease management, are part of its allure. These difficulties elevate its status from a mere houseplant to a prized botanical specimen, attracting enthusiasts who seek to master the art of growing truly unique and demanding species. The scarcity of detailed information on this particular fern further emphasizes its rarity, making any successful cultivation a significant achievement and a valuable contribution to horticultural knowledge. Ultimately, nurturing Platycerium quadridichotomum is not just about growing a plant; it is about appreciating a unique natural wonder and fostering its enduring beauty through dedicated care.

If i die, water my plants!