I’ve spent years growing, observing, and experimenting with a wide range of plants. Among the many that have captured my attention, Vaccinium Angustifolium, commonly known as Lowbush Blueberry, holds a special place in my heart. This plant is native to North America and thrives in acidic, well-drained soils. Here, I’ll walk you through the most common questions I get about it, based on my personal experience.

488 Species in Genus Vaccinium

What is Vaccinium Angustifolium, and Why Do I Grow It?

Vaccinium Angustifolium is a dwarf, spreading shrub that produces tiny, intensely sweet blueberries. It’s a cold-hardy, rhizomatous plant that often forms dense colonies. I grow it because it’s tough, requires little maintenance once established, and delivers nutrient-rich berries loaded with antioxidants like anthocyanins and flavonoids.

What stands out to me most is its adaptability. It handles drought better than other berry species and survives winters that drop well below zero. It also doubles as groundcover, adding both function and aesthetic appeal to my garden.

How Does Vaccinium Angustifolium Compare to Highbush Blueberries?

Many people ask me whether they should plant Lowbush or Highbush (Vaccinium Corymbosum) blueberries. I’ve grown both, and here’s what I’ve found:

- Size: Lowbush plants grow only 6 to 24 inches tall, while Highbush can reach 6 feet. If you want a tidy ground layer, go with Angustifolium.

- Flavor: The Lowbush berries are smaller, but they pack a punch. More sugar, more tang, and more antioxidants per gram. I often describe them as nature’s candy.

- Yield: Highbush gives more berries per plant, but Lowbush thrives in marginal soils and forms productive colonies over time.

- Care: Highbush requires more pruning and fertility. I’ve found Lowbush to be far less demanding.

In short, if you want ease and flavor, go Lowbush. If you want volume and vertical presence, go Highbush.

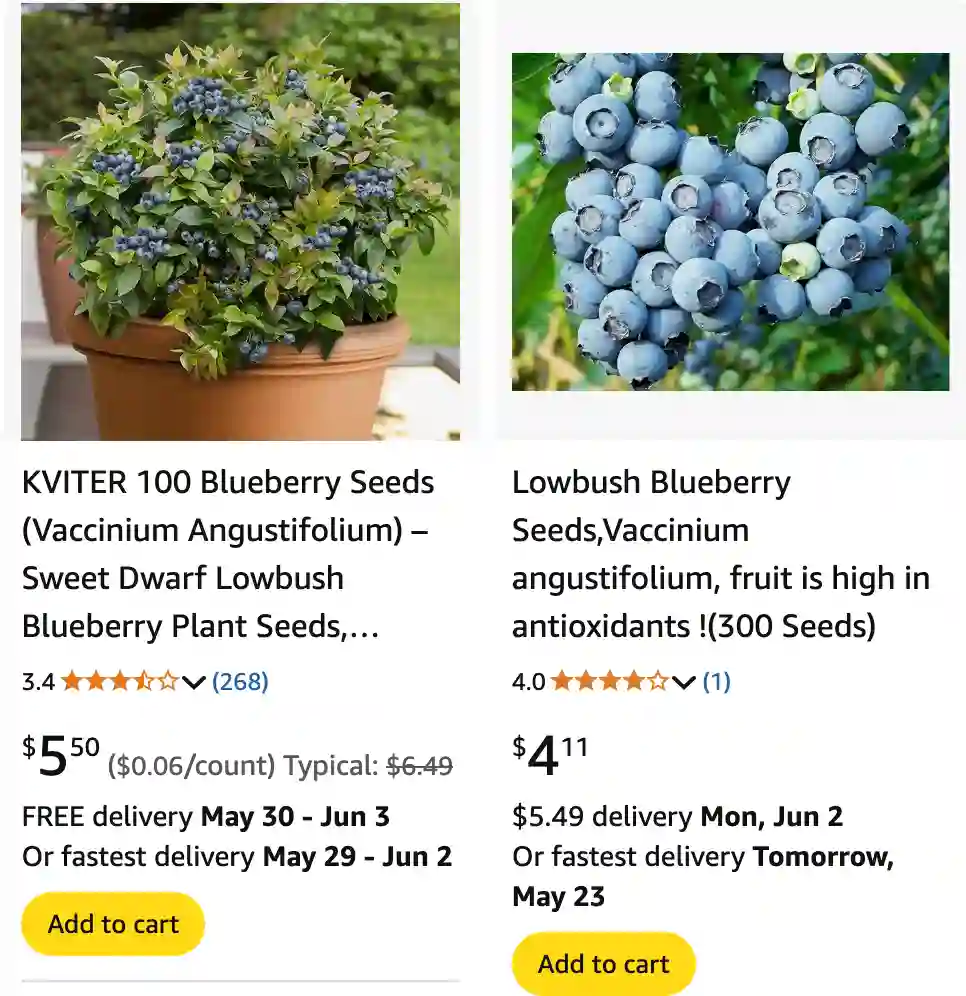

Can Vaccinium Angustifolium Grow in Containers?

Yes, and I’ve done it. But it takes some tricks. First, you must ensure acidic soil—ideally between pH 4.2 and 5.5. I use a mix of peat moss, pine bark, and perlite. Second, the container should drain well. Lastly, these plants crave sun. Give them at least 6 hours of direct light.

Fertilize lightly, using organic options like cottonseed meal. I’ve also top-dressed with pine needles to keep the soil acidic and mimic their natural habitat.

How Do I Propagate Vaccinium Angustifolium?

I’ve successfully propagated it using rhizome divisions. In spring or fall, dig up a portion of the underground runner and replant it in acidic, sandy soil. Water it well for the first few weeks. You can also use softwood cuttings, though I’ve found that method trickier.

Unlike some ornamental shrubs, this one doesn’t mind being divided. In fact, it thrives on it. Over time, colonies will fill in and form dense mats, perfect for erosion control or underplanting around trees like Pinus Strobus.

Is Vaccinium Angustifolium Good for Wildlife?

Absolutely. I’ve watched pollinators—especially native bees—flock to the flowers in early spring. Birds love the berries just as much as I do. It’s also a host plant for several species of moths and butterflies, including the Blueberry Gray (Glena cognataria).

If you’re creating a native plant garden or food forest, it checks all the boxes: biodiversity, aesthetics, and function.

Can It Be Used Ornamental Landscaping?

Yes—and I often recommend it. It’s not just edible. The foliage turns fiery red in fall, giving it ornamental value that rivals many Japanese maples. It also blends beautifully with other acid-loving plants like Kalmia Latifolia, Rhododendron Maximum, or Gaultheria Procumbens.

I’ve used it in rock gardens, borders, and even as a transition between forest and lawn. Its low profile makes it excellent for understory plantings in naturalistic settings.

What Are Common Problems with Vaccinium Angustifolium?

From my experience, it’s relatively disease-resistant. But I’ve still faced a few issues:

- Mummy Berry (Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi): Rare in wild populations, but possible in wetter areas. Avoid overhead watering.

- Root Rot: Only if drainage is poor. That’s why I stress well-drained, sandy soil.

- Bird Damage: They’ll eat every berry if you don’t net it.

My advice? Mimic its natural habitat. That’s how I’ve avoided most problems.

What’s the Best Way to Harvest and Use the Berries?

I handpick them in mid-to-late summer when they turn deep blue. I dry some, freeze others, and eat plenty fresh. Their glycemic index is low, and they’re packed with Vitamin C, fiber, and polyphenols.

One of my favorite things is to dehydrate them and toss them into homemade granola. They also make killer jam—much better flavor than cultivated blueberries.

Final Thoughts: Why I Always Recommend Vaccinium Angustifolium

If you want a plant that delivers beauty, resilience, and bounty with very little input, this is it. In my experience, Vaccinium Angustifolium punches far above its weight. Whether you’re a native plant purist, a wildlife gardener, or just someone who loves good fruit, you won’t regret growing it.

If i die, water my plants!